Separate from the Start

A long history of exclusionary policies and practices created unequal housing opportunities in Virginia.

The stories below will help you fully understand the context of our challenges, and explain to others how we got to where we are today.

- Early Virginia through Reconstruction

- Early 20th Century

- Post-War and Civil Rights Era

- Predatory Lending and Foreclosure Crisis

- COVID-19 and the Post-Pandemic Economy

Early Virginia through Reconstruction

The history of housing in Virginia and the United States at large is founded on inequality. Legalized slavery prevented enslaved people from owning or renting property for over 200 years, and indigenous peoples were displaced from their homes to make room for new settlers.

By the start of the Civil War, Virginia had the largest enslaved population of any Confederate state. Following the war and the end of chattel slavery, legislation during Reconstruction expanded civil rights to persons of all races, including the right “to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property.”

Unfortunately, these new rights would not last long. In 1883, the Supreme Court struck down major portions of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, effectively legalizing racial discrimination by private citizens, businesses, and organizations. Housing segregation became the de facto law of the land across much of the nation. The right that existed on paper to buy and lease property free from discrimination would remain out of reach for nearly another century.

Early 20th Century

In Virginia, as in many states, Black Codes and Jim Crow laws further terrorized Black families into the 20th Century. These allowed additional means of institutional segregation throughout housing markets. In Virginia, this was accomplished in three major ways: exclusionary zoning ordinances, racially restrictive covenants, and mortgage discrimination.

Exclusionary zoning

In 1911, the City of Richmond became the first locality in Virginia to codify separate areas for white and Black residents. Soon after, the General Assembly granted this authority to all cities and towns in the state. Many communities quickly adopted similar ordinances, establishing “segregation districts” to secure white-only neighborhoods.

The Supreme Court struck down these racially-motivated zoning districts as unconstitutional in 1917. Not long after, the 1926 landmark Euclid v. Ambler decision paved the way for local governments to regulate the use of land and buildings for “public welfare.”

While explicitly racist ordinances were forbidden, local leaders quickly found ways to use this broad authority to achieve the same ends. Comprehensive planning efforts to guide future development patterns, created with the aid of professionally trained planning consultants, were acutely driven by segregationist goals.

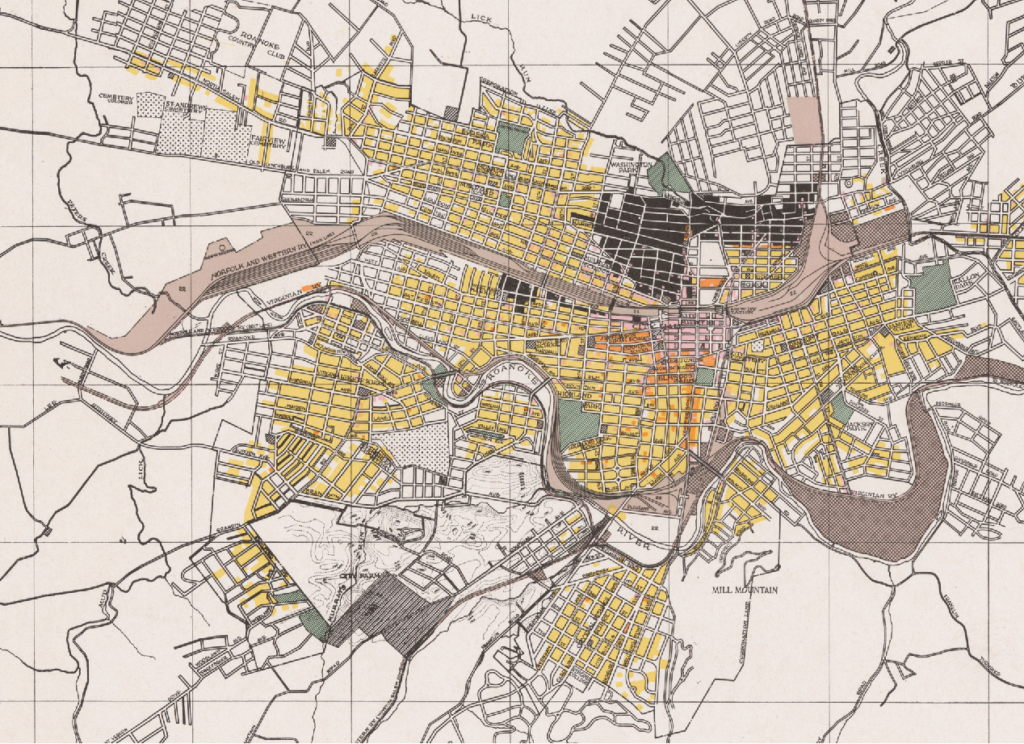

For example, Roanoke’s city plan from 1928 did not make any special designations for existing Black neighborhoods, but provided clear residential protections to white areas. In effect, this preserved white areas while opening up Black neighborhoods to redevelopment and displacement.

Likewise, Alexandria’s first zoning map refused to award a residential designation for predominantly Black neighborhoods, instead classifying these areas as industrial. This assignment would justify future redevelopment—and displacement—in the future.

Perhaps the most enduring elements of these first generation zoning ordinances are districts that allow only single-family homes. Larger, detached homes would be unaffordable to Black and low-income residents, cementing lines of segregation without explicitly racist language.

Additional resources

Zoning and Segregation in Virginia: Part 1 (McGuireWoods)

Zoning and Segregation in Virginia: Part 2 (McGuireWoods)

The Racial Origins of Zoning in American Cities

Racial covenants

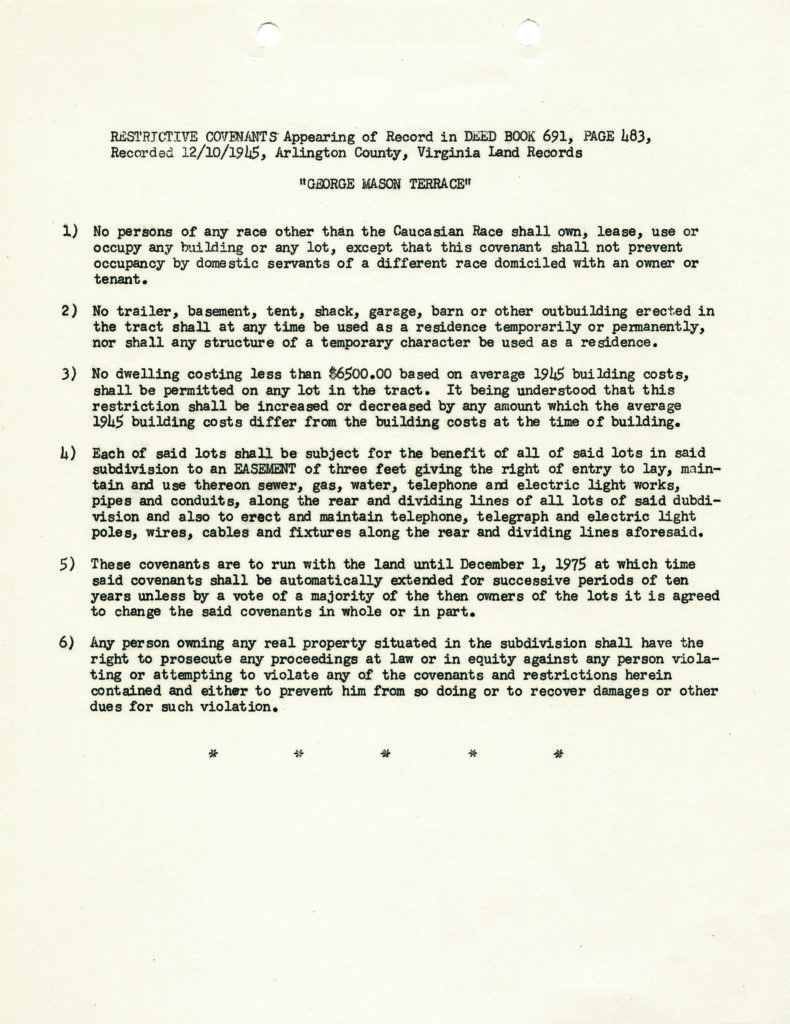

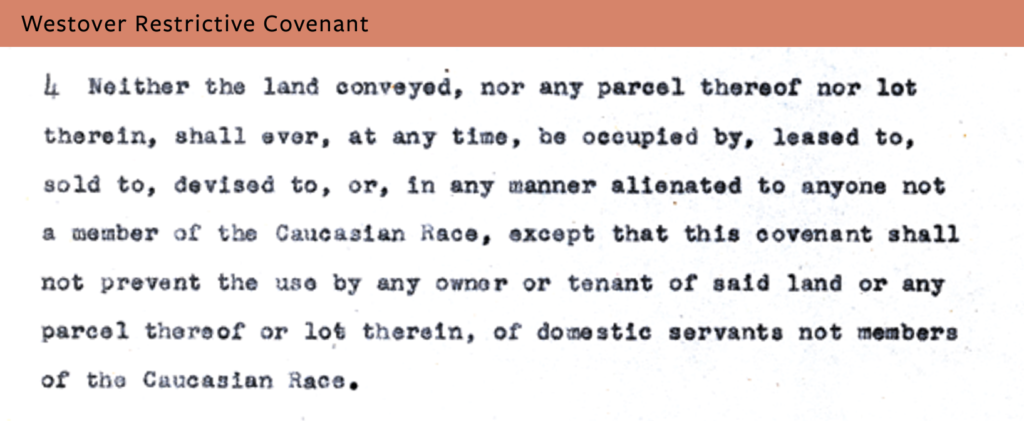

The Supreme Court’s rulings in the late 1800s paved the way for rampant segregation enacted by private citizens. Beginning the 1920s, as residential development began to expand beyond the city and into the suburbs, white property owners began to regularly insert racial covenants into their deeds. These created legally binding prohibitions against the sale or occupation of that property to any person who was not white.

What are racial covenants?

Racial covenants are clauses inserted into property deeds that restrict the ownership and occupancy of a home to white persons only.

Over the next three decades, developers and homeowners associations promoted these covenants with the intention of permanently barring the presence of Black, Asian, Hispanic, and Jewish persons.

In 1948, the Supreme Court held in Shelley v. Kraemer that racial covenants were unenforceable. While this decision nullified all existing covenants, they would not be fully prohibited until the Fair Housing Act in 1968.

Today, these covenants can still be found in many property deeds throughout the state. In recent years, homeowners and researchers have steadily uncovered and tracked deeds with racial covenants. Such efforts can be found in Albemarle County, Arlington County, and Richmond.

In an effort to make it easier for property owners to legally remove these racist clauses, state lawmakers passed a bill in 2020 that requires court clerks to reject deeds with racial covenants and to remove them when requested by the property owner.

Additional resources

Deeply Rooted: History’s Lessons for Equity in Northern Virginia (VCU Center on Society and Health and Northern Virginia Health Foundation); Deeply Rooted Report

Mapping Prejudice (University of Minnesota Libraries)

Mortgage discrimination

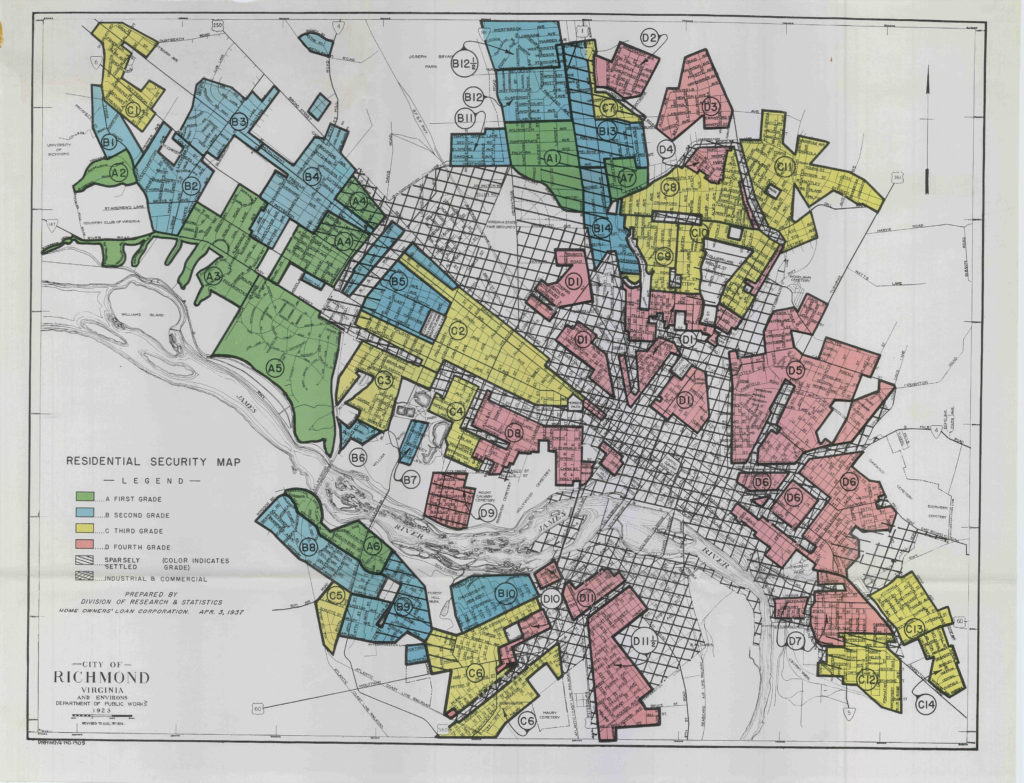

The government-sponsored Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) was created during the New Deal to acquire and refinance distressed mortgages. To assess the underlying risk of home loans across communities, HOLC created a series of “residential security maps” of major cities from 1935 to 1940.

These maps assigned one of four risk categories to each neighborhood. Newer, affluent “Type A” neighborhoods would be outlined in green, while lower-performing but acceptable “Type B” and “Type C” neighborhoods would be blue and yellow, respectively. The riskiest “Type D” neighborhoods were marked red.

In Virginia, HOLC produced security maps for four areas: Lynchburg, Richmond, Roanoke, and Greater Norfolk (including the cities of Hampton, Norfolk, Newport News, and Portsmouth). HOLC’s maps from across the state—and throughout the nation—consistently assigned the highest risk to neighborhoods with the highest concentration of Black residents.

These designations reveal how pervasive racial discrimination was among the local real estate professionals HOLC employed to produce the maps. Today, the red color used by HOLC to brand “undesirable” neighborhoods is now immortalized in the term “redlining.”

What is redlining?

Redlining is the intentional withholding of financial, health, and other services from certain neighborhoods. This discrimination is most often targeted against communities with racial and ethnic minorities, particularly those with less wealth and lower incomes.

However, despite common belief, HOLC did not use these maps to deny mortgages in redlined communities. They were produced well after HOLC ended its lending activity; in fact, HOLC did purchase many distressed mortgages from Black homeowners.

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), however, was prolific in its efforts to withhold lending capital to Black neighborhoods. Redlining was enshrined in the FHA’s underwriting manuals, requiring lenders and insurers to be complicit in this systemic denial. Between 1934 and 1962, only two percent of all the loans guaranteed by the FHA went to Black homeowners.

The FHA had committed to this discrimination well before HOLC completed its maps. Still, they prepared their own maps to guide these race-based lending policies, and many were likely inspired by HOLC’s efforts. Unfortunately, a more precise understanding of this connection is impossible today: nearly all FHA maps were destroyed by the agency in 1969 in response to a civil rights lawsuit.

Post-War and Civil Rights Era

Efforts to maintain and expand residential segregation continued after World War II. With exclusionary zoning and racial covenants as a foundation, the FHA accelerated its public subsidization of white-only homeownership, particularly in the growing suburbs.

Physical destruction and displacement of Black communities in cities also became commonplace. Justified by “rational” planning, highway construction, and “slum clearance,” these urban renewal activities were a major influence on the eventual adoption of the Civil Rights Act and other anti-discrimination efforts at a level not seen since Reconstruction.

Urban renewal

Fueled by booming suburbs, nationwide efforts to reshape urban cores into highways and other uses catering to white commuters were in full swing by the 1950s. A side effect—and often the main rationale—of these “renewal” efforts was the destruction and forced isolation of Black neighborhoods.

What was “Urban Renewal?”

“Urban renewal” referred primarily to public efforts between the 1940s and 1970s to revitalize aging and decaying inner cities, although some suburban communities undertook such projects as well. Including massive demolition, slum clearance, and Interstate Highway development, urban renewal policies displaced thousands of communities and re-shaped cities across the country. Examples of significant urban renewal projects in Virginia include the removal of large parts of the Fulton Bottom and Jackson Ward neighborhoods in Richmond, the removal of the Gainsboro neighborhood in Roanoke, and the removal of Harrisonburg’s Newtown.

Flush with federal dollars for highways and redevelopment, many cities in Virginia began systematically targeting Black neighborhoods for “renewal.”

- Jackson Ward, Richmond

- Battered by demolition and displacement, Jackson Ward stands strong at 150th anniversary (Richmond Times-Dispatch)

- Gainesboro, Roanoke

- The Urban Renewal of Gainsboro (R.R. Wilkinson Foundation)

- Fulton, Richmond

- Indelible Roots: Historic Fulton and Urban Renewal (Virginia Public Media)

- Newtown, Harrisonburg

The best weapon local officials could use to march these projects forward was eminent domain. While the Fifth Amendment instructs the government to provide “just compensation” to property owners when their land is taken for “public use,” these terms were often twisted to specifically target the taking of Black-owned property with little course for remedy.

What is eminent domain?

Eminent domain is the power of the government to take private property and convert it to public use, often used in tandem with other urban renewal projects in the 20th century.

According to research by the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond, at least 7,500 families of color were displaced by urban renewal projects in Virginia from 1950 to 1966—more than four and a half times the number of white families displaced.

Additional resources:

History of Urban Renewal (Encyclopedia of Chicago)

Renewing Inequality: Urban Renewal, Family Displacements, and Race 1950-1966 (Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond)

Eminent Domain and the Displacement of Black Communities (VCU Center on Society and Health and Northern Virginia Health Foundation)

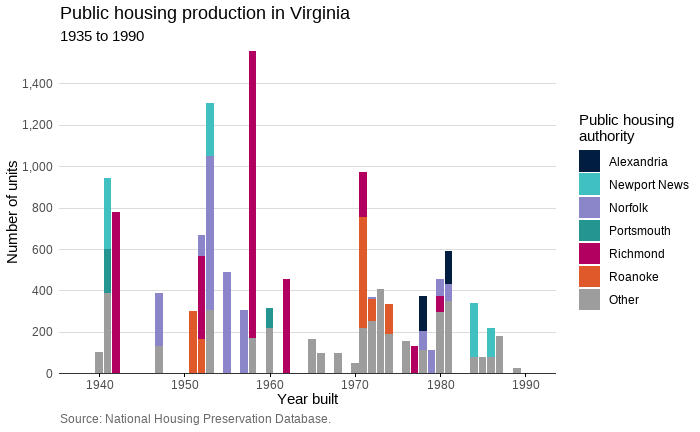

Public housing

While public housing projects today mostly bring to mind lower-income families of color, public housing was originally born of New Deal idealism and Great Depression-era public works programs to replace slums and provide workforce housing for white workers. These early developments were called “sanitary housing,” as a way to affirm the goals of improved and safe housing for workers. Public housing sites were determined based on the level of blight in an area. If a neighborhood was deemed a “slum” by the local housing authority, it then used eminent domain to clear the land and construct public housing.

Eminent domain was often used by Virginia housing authorities to select private properties that were poorly-maintained and close to the commercial districts. This almost always meant that Black people’s homes were chosen for demolition, as in the examples listed above, and Black homeowners were often underpaid for their land. While the original tenants of public housing were mainly White, by the 1940s, public housing became an effective mechanism for isolating and controlling Black communities.

A tale of two cities’ public housing

Richmond

The Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority (RRHA) was formed in 1940. Its first major public housing initiative was Gilpin Court, which opened in 1943. The creation of Gilpin and subsequent projects in the following decades was motivated by the idea of demolishing “Black slums” in the city, most without indoor plumbing, and replacing them with new, healthier buildings. While the idea was paraded as a moral victory and an improvement, the entire development process was one-sided, with RRHA determining which neighborhoods were valuable and worth preserving and which were beyond repair. This process, in tandem with other urban renewal initiatives that destroyed Jackson Ward and other Black enclaves in Richmond, resulted in segregation and highly concentrated poverty that persists to this day.

Additional resources for Richmond

How Did We End Up Here? A brief history of public housing in Richmond [Richmond Magazine]

A Public History of Public Housing: Richmond, Virginia [Yale National Initiative]

Norfolk

Norfolk was one of the first two cities to receive public housing funding under the Federal Housing Act of 1949. Through this funding, the nation’s first redevelopment project was begun in Norfolk in 1951 at Tidewater Gardens. Although Norfolk was heralded as a national model for housing redevelopment in the 1960s, these early projects were still racially segregated, along with most other housing in the area, which made it much harder for Black people to find private accommodations and transition out of public housing. Changes in federal policies over the latter half of the 20th century, including lower income requirements, helped cement these public housing communities as dense pockets of poverty.

Additional resources for Norfolk

NRHA History [NRHA]

How Norfolk became segregated: the century-long roots of the city’s ‘Dividing Lines’ [The Virginian-Pilot]

According to data from HUD, 78% of all persons living in Virginia’s public housing units today are Black. Public housing projects are both socially and physically isolated from the rest of cities, cutting off residents from cultural and economic opportunities. While public housing was ushered in with intentions of improving quality of living for lower-income workers, they have seen a steady decline in investments and an intentional abandonment by policymakers over generations that has left many units in disrepair and dangerous to residents’ health.

Today, as the urban cores of Virginian cities have become more in-demand as places to live and work, many of these early public housing developments are being eyed for redevelopment plans that offer little to no replacement for public housing units, threatening to repeat the cycle of displacement for non-white residents.

Repeating the cycle of displacement: Tidewater Garden’s abandonment and redevelopment

Additional resources

Hijacking Public Housing: A Review of New Deal Ruins [Southern Spaces]

How Public Housing Was Destined to Fail [Greater Greater Washington]

Federal action on Civil Rights

Although the federal Fair Housing Act of 1964 finally made discrimination in housing illegal, including the common practices of blockbusting and racial steering, government agencies were divided on how to enforce it. The Nixon administration prohibited what it viewed as “imposed economic integration,” insisting that suburban opposition to low-income housing could be attributed to nonracial considerations, such as fear of “lowering property values and bringing in . . . a contagion of crime, violence, [and] drugs.” As a result, the Equal Housing Opportunity policy began to distinguish between illegal racial discrimination against specific individuals and legal economic segregation caused by market forces and zoning policies.This had ripple effects on the state level, and Black Virginians faced exclusion and ostracization from the growing suburbs outside Alexandria, Richmond, and other large urban centers facing “white flight.”

Throughout the 1970s, Civil rights groups launched litigation campaigns against exclusionary zoning in the suburbs, but a series of pivotal Supreme Court decisions effectively endorsed the distinction between illegal racial segregation and legal economic discrimination; these decisions made exclusionary zoning an almost insurmountable obstacle for the civil rights movements nationwide.

Nevertheless, congress continued to pass measures to chip away at structural discrimination in the housing industry. These included the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) of 1974 and the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) of 1977.

Spotlight: Housing Opportunities Made Equal of Virginia

The persistent impacts of racial disparity in housing and homeownership opportunities throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries kept many non-white families from securing opportunities to build generational wealth. While unable to match the income and credit levels of their white counterparts, non-white Virginians still sought the American dream of homeownership. That desire was exploited by an abundance of predatory practices, including subprime lending, which were major factors in the housing and financial crisis of the late 2000s.

Predatory Lending and Foreclosure Crisis

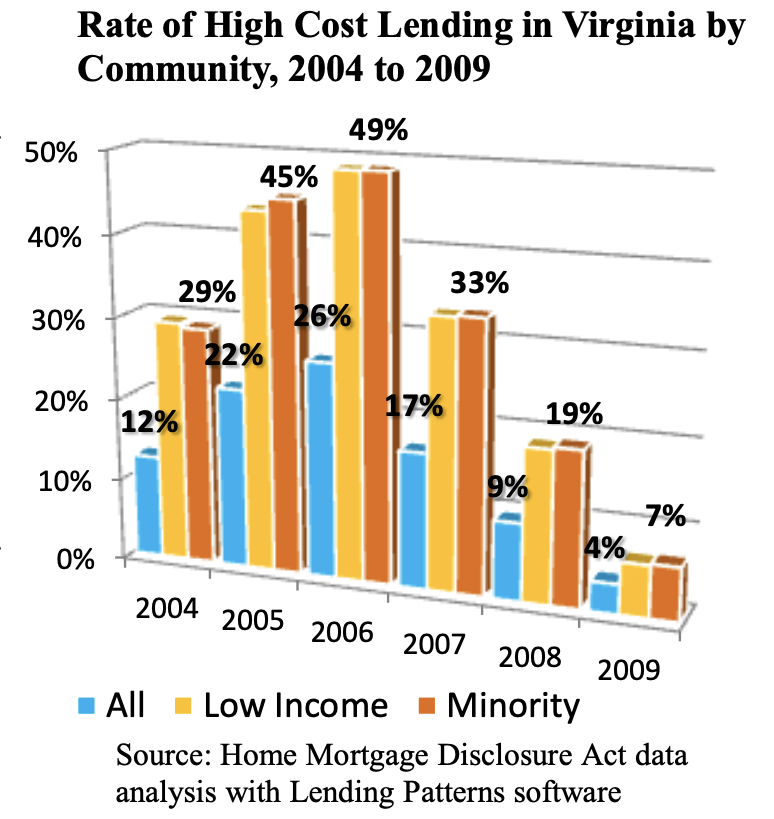

The financial crisis of 2007–2010 stemmed from an expansion of mortgage credit through subprime lending to borrowers who previously had difficulty getting mortgages, including many people of color. Historically, potential homebuyers found it difficult to obtain mortgages if they had below average credit histories, provided small down payments, or sought high-payment loans;. In the early and mid-2000s, however, high-risk mortgages were made more available by lenders, who repackaged them into securities and sold them to investors.

Subprime mortgages

Economists now cite the collapse of the subprime mortgage market—mass defaults on high-risk housing loans—as one of the most significant contributors to the 2008 financial crisis. Fraudulent activity in the mortgage industry leading up to the market crash was widespread, with nearly half of the sixty largest firms in the market engaged in widespread securities fraud and predatory lending. This involved finding borrowers who would take on risky, nonconventional loans with high interest rates that would benefit the banks, or through steering homeowners who qualified for conventional, prime loans into subprime loans. Although financial institutions preyed on low-income, elderly, and non-white communities, their efforts were particularly concentrated in communities of color. Studies show that people of racial and ethnic minorities were subjected to predatory loans more so than whites. Lenders issued high cost loans to 58%of low-income Black borrowers and to 37% of low-income Latine borrowers, as compared to only 28% of low-income white borrowers. Discretionary pricing and lack of transparency in the subprime market often resulted in inefficient, confusing, and unfair loan prices.

How did predatory lending target Virginia’s minorities?

Data shows Big Racial Disparities in Mortgage Loans and Homeownership [Virginia Mercury]

Victimizing the Borrowers: Predatory Lending’s Role in the Subprime Mortgage Crisis [Wharton School, UPenn]

Foreclosures

In the wake of the housing crash came a prolonged wave of foreclosures that disproportionately affected those with the highest-risk loans and the least financial stability. Foreclosure rates skyrocketed in 2007, with the highest amounts seen in 2009 and 2010 at 60,000+ homes foreclosed on each year. Foreclosure rates did not significantly diminish in Virginia until 2011, leaving the state with over five years of significant loss in the housing sector.

Foreclosures affected Virginia’s housing market in two specific ways. First, foreclosures led to vacancies, which correlated with increased vandalism, crime, and the continued downward spiral of property values in communities. Second, the surplus of vacant homes exerted tremendous downward pressure on home prices throughout the Commonwealth. From 2007 to the end of 2011 the median home sale price declined by 21%. This two‐pronged attack on property values put homeowners throughout the Commonwealth “underwater”— owing more on their mortgages than their home was worth. Nationwide, the foreclosure crisis disproportionately affected Black and Latine borrowers, who were 76% and 71% more likely, respectively, to have lost their home to foreclosure than non-Hispanic white borrowers.

Minority homeownership barriers

In response to the crash of the subprime market, the industry significantly restricted lending, making it more difficult for the average borrower to get a loan; people of color continued to face disproportionate prime loan denials.

Of the approximately 14,700 mortgage loan applications submitted by Black Virginians in 2019, 11.9% were turned down. In contrast, of the roughly 70,400 applications from non-Hispanic white Virginians, only 5% were rejected. The denial rates were 9.6% for Hispanic applicants and 8.5% for applicants of Asian descent. These trends did not change in 2020, as shown in the dashboard below.

These racial disparities existed even among applicants with similar income levels, according to data collected under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act. For example, among applicants with annual incomes of about $125,000, the denial rates were 8.4% for Black Virginians and 3.6% for non-Hispanic white applicants, or less than half the rate of denial for Black applicants.

Loan denial rates in Virginia vary not only by race but also by geography, and in at least 25 cities and counties, the denial rate for Black applicants is more than triple the rate for white applicants. The two most important factors in these loan denials, debt-to-income ratios and credit history, are tied to the long-term difficulties in building and maintaining wealth for people of color.

Considering things like generational wealth and assets, research shows that white families have eight to ten times the amount of wealth as Black families. Biases in lending practices based on these markers of generational inequity contribute to denials across the Commonwealth, and communities that do not have adequate access to financial services lack down-payment assistance.

Additional resources

Mortgage Lending in the City of Richmond: Analysis of Lending Patterns [HOME of Va.]

COVID-19 and the post-pandemic economy

Only ten years after the Foreclosure Crisis finally subsided in most states (including Virginia), the world was plunged into uncertainty once more with the outbreak of the global COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Unemployment in Virginia rose to 11%, with 5,000 people dead and 18,000 hospitalized in 2020 alone. COVID-19 hospitalization rates have been higher for the Hispanic and Black populations than for other racial and ethnic groups in the state. When compared to the COVID-19 hospitalization rate for white Virginians from 2020-2021, the rate was 2.0 times higher for Black Virginians and 2.6 times higher for Latin American Virginians.

Although Virginia’s unemployment rates were highest in 2020, overall joblessness remained above 4% through 2021 and even higher in certain populations. By September 2020, 59% of Latin American renter households and 53% of Black renter households reported income losses due to unemployment, according to analysis of the Census Bureau’s weekly Household Pulse Survey.

The COVID-19 pandemic had an uneven impact on housing. Many renters fell behind or experienced lags in their unemployment assistance, fearing eviction (despite the Federal moratorium). Meanwhile, owner-occupied home values skyrocketed with increased demand brought by the combination of low interest rates, high rents and remote work that pushed others to buy their first home.

These disparities in housing market outcomes reflected the pandemic’s uneven impact on labor markets, with college-educated professionals working from home and building equity, while low-wage service workers, often renters, faced the highest rates of job loss. As of the first quarter of 2022, unemployment remained at 6% for Black Virginians and 4% for Latin American Virginians while it has fallen to 2.2% for white Virginians.

A shortage of available single-family homes in Virginia is continuing to drive up prices and slow sales through the summer of 2022, raising the likelihood of long-term affordability issues that could slow the state’s growth. The rental market is also experiencing price increases that are further burdening renters who have been catching up on job changes over the last two years. Cities such as Richmond have experienced a 22% increase in average rents since 2020.

The RVA Eviction Lab’s 2022 first quarter report cited data from a U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey of Virginians who were behind on rent, estimating that about 58% of Virginia renter households feared eviction in the next two months. Approximately 52% of those surveyed behind on their rent payments, compared to 16% at the end of 2021.

Renters today are normally tomorrow’s first-time homebuyers—but not with a mountain of rent debt and an eviction on their record. The pandemic has worsened income inequality, and the long-term ramifications are likely to make it even harder for at-risk renters to find and retain affordable housing options as demand increases.

Additional resources

Black and Hispanic Renters Face Greatest Threat of Eviction In Pandemic [Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University]

What the Great Recession Can Teach Us About The Post-Pandemic Housing Market [Brookings Institute]

The Extraordinary Wealth Created by the Pandemic Housing Market [The New York Times]