The FWD #235 • 970 words

Virginia’s Independent Cities Impact Housing Development

Virginia’s unique system of independent cities creates a distinct landscape for affordable housing that shapes development possibilities throughout the Commonwealth.

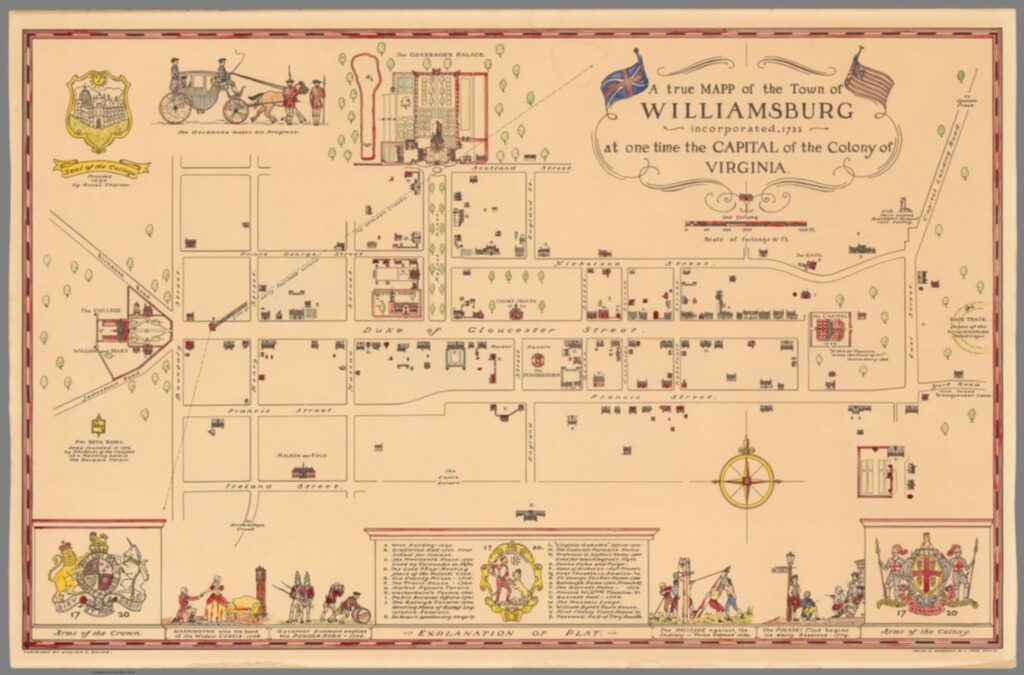

Did you know that Virginia stands alone in the United States with its system of 38 independent cities that operate completely separate from surrounding counties? This governmental quirk—which began with Williamsburg’s incorporation in 1722—creates a situation where cities function with complete political and administrative independence from neighboring counties.

For housing developers and advocates, this raises an important question: Does this unusual structure help or hinder affordable housing efforts?

These “include“, Baltimore, Maryland; St. Louis, Missouri; and Carson City, Nevada.

We’re Different

Unlike virtually every other state where cities exist within counties, Virginia’s independent cities maintain their own governments, tax structures, and—critically for housing development—their own land use and zoning authority. When a property sits within city limits, the city (not the county) has complete jurisdiction over zoning decisions, building permits, and development approvals.

This separation creates a patchwork of different rules across adjacent jurisdictions that affordable housing developers must navigate. It also creates confusion when we talk to housing experts outside the Commonwealth.

Our Counties Are a Little Odd, Too

Virginia’s 95 counties add their own governmental complexity to the housing landscape. Unlike the relatively uniform structure of independent cities, counties can operate under seven different forms of government outlined in state code. Each of these forms has distinct administrative capabilities and decision-making processes:

- County Commission: “Traditional” form dating back to 1870 Constitution. Used by most (84) counties. An elected Board of Supervisors runs the government, but usually appoints a county administrator.

- County Manager Plan: Adopted by Arlington County in 1930 after special legislation from the General Assembly. Developed in response to growing urbanization, this model incorporates certain elements of independent city governance.

- County Manager Form: Enabled by the state in 1932 and adopted by Henrico County two years later. Similar but distinct from County Manager Plan, it creates a county manager position with wide-ranging authority.

- County Executive: Created alongside County Manager Form; adopted by Albemarle County in 1933 and, many years later, by Prince William County in 1972. County executives have slightly less powers than county managers.

- County Board: Authorized in 1940 and currently used by three very rural counties: Carroll, Russell, and Scott. Similar to County Commission, but requires a county administrator position.

- Urban County Executive: Created in 1960 specifically for rapidly-growing Fairfax County; includes tweaks to County Executive option.

- County Charter: The newest county government option created by the General Assembly in 1985. Creates actual charters akin to cities and towns, providing much greater flexibility to govern and design local policy—but still within the bounds of the Dillon Rule. In use by Roanoke County (1986), Chesterfield County (1987), and James City County (1993).

These structural differences affect housing policy in meaningful ways. Counties with professional managers or executives may have greater administrative capacity to navigate complex affordable housing programs and coordinate with state agencies. Traditional commission counties might rely more heavily on individual supervisor relationships and may face resource constraints in housing program administration.

The form of government also determines fiscal flexibility. Chartered counties have special legislative authority that could, in theory, more easily enable innovative housing financing approaches. Meanwhile, other counties must operate with a policy framework where the General Assembly wields much greater control.

Challenges Created by City Independence

The independent city system creates several significant obstacles for housing development:

Fiscal pressures: Cities bear responsibility for a wide range of services including schools, social services, and public safety. These pressures often lead cities to prioritize commercial development with higher tax revenue over affordable housing projects, which might generate less revenue relative to the services new residents require. Cities in Virginia often have more residents with significant needs, requiring greater investment in social and municipal services.

Fragmented planning: The sharp boundaries between cities and counties create artificial barriers to coordination. While housing markets operate regionally (with people living in one jurisdiction and working in another), the independent city system can promote competition rather than collaboration on housing solutions.

Jurisdictional complexity: Developers working across multiple localities face different application processes, fee structures, and zoning requirements. This jurisdictional complexity adds time and cost to affordable housing development, especially for regional organizations trying to address housing needs across city-county boundaries.

Siloed resources: State and federal housing resources often flow separately to cities and counties, potentially reducing efficiency and coordination. What might be accomplished through one larger, coordinated effort instead becomes multiple smaller initiatives with their own administrative overhead.

The challenges of operating an independent city can be seen throughout Virginia when cities like Bedford, South Boston, and Clifton Forge have given up their independent city status in favor of operating as a town.

Moving Forward: Regional Solutions

The most promising approaches involve regional cooperation that transcends the city-county divide. The Richmond Regional Housing Framework demonstrates how independent cities and counties can work together to address affordable housing needs across jurisdictional boundaries.

For affordable housing strategies to succeed in Virginia, they must work within or around our unique governmental structure by:

- Leveraging city autonomy to implement innovative housing policies

- Creating regional housing authorities that bridge city-county divides

- Developing state-level incentives promoting coordination

- Building community support regardless of jurisdictional boundaries

Virginia’s independent city system is neither inherently good nor bad for affordable housing—it’s a distinctive context that shapes possibilities and challenges. Success depends less on the structure itself and more on how effectively housing advocates, developers, and policymakers navigate this unique landscape to create homes everyone can afford.