The FWD #208 • 665 Words

America’s love affair with cars is having significant impacts beyond where the rubber meets the road.

For those of us in the housing world, much of our focus on zoning relates to the types and amount of housing that can be built. But the way many American localities zone has also contributed to making transportation our second greatest expense.

Long commutes, traffic congestion, and personal vehicle maintenance have a major impact on our ability to afford rent or a mortgage because first and foremost, people need a way to reach work and life’s other necessities. And while the rent eats first, the gas tank comes second.

The strict separation of uses has led to car-dependency and car-centric patterns of development. Wide roads move cars quickly and efficiently from one place to the other, with surface parking lots at either end of the journey. And along the way, you’ll hardly see a sidewalk, let alone a bus on the road.

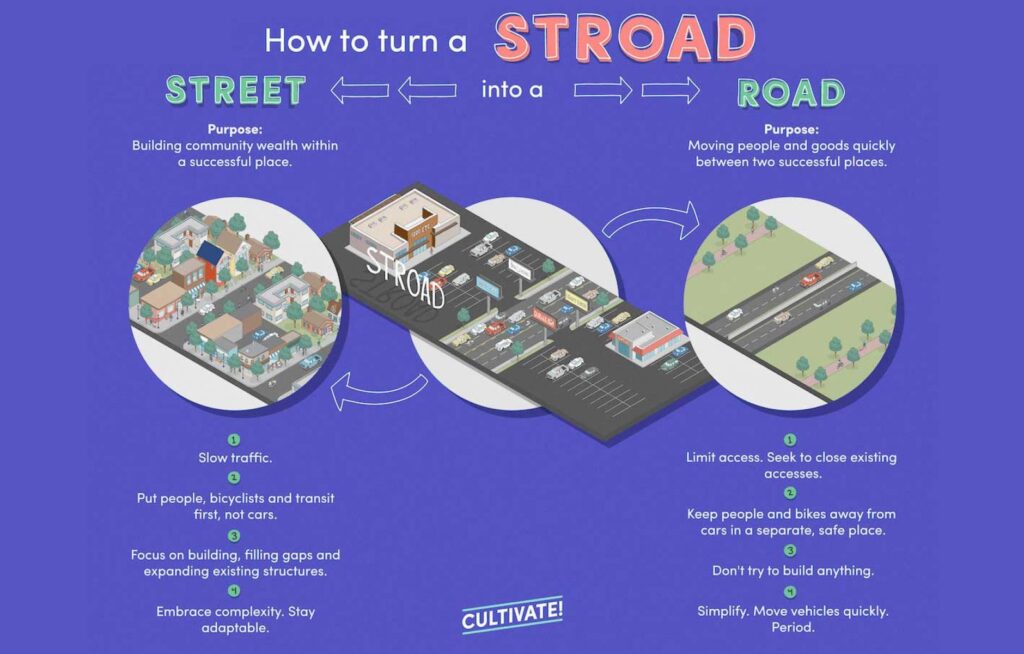

These wide, multi-lane avenues, called “stroads” by some, have proliferated across the country. Stroads attempt to serve as both high-speed roads and accessible urban streets, but end up failing to be either. And zoning plays a big part in preventing human-scale development along them.

Transit-oriented development (TOD) has arisen as an important strategy to fight high transportation and housing costs by co-locating more compact forms of housing and commercial uses with stations on a fixed-route transit line. The combination of density, walkability, and affordability can create more equitable neighborhoods. It’s not just a trend in big cities with lots of transit either; TOD is also supporting small and rural communities across the nation.

People over parking

While cars will likely remain an integral part of life for most Americans, we can design more car-lite communities, where people can opt to drive less, own fewer vehicles, or forgo car ownership entirely. As Henry Grabar shares in his book Paved Paradise, “[in the U.S.] more square footage is dedicated to parking each car than to housing each person.” There is a growing movement to turn more and more surface parking lots into housing.

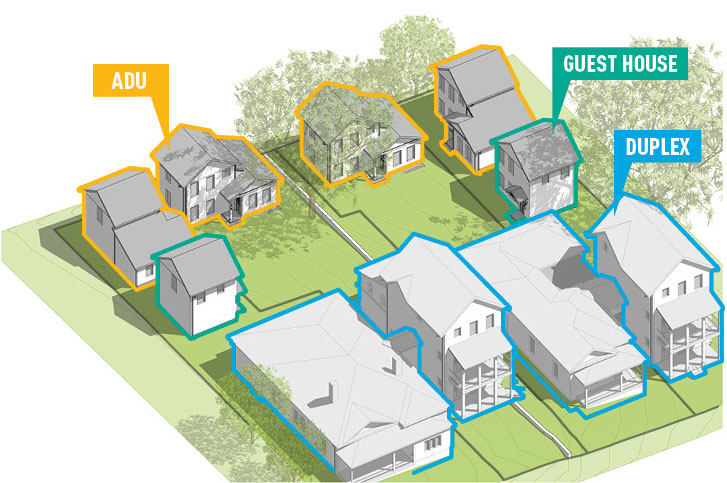

More and more, communities are finding creative ways to integrate transit-oriented density into existing neighborhoods, such as Finley Street Cottages in eastern Atlanta. The property fits 17 homes onto 0.69 acres of land within a 15-minute walk or 5-minute bike ride of two MARTA metro stations, parks, neighborhood stores and services. The site’s density was raised sixfold while maintaining the neighborhood’s scale— a good example of sensitive Missing Middle housing.

Losing the “Human” Scale

Car-centric development leads to major impacts on community health. The mechanisms aren’t limited to pollution or sedentary lifestyles; pedestrian deaths from car crashes are also reaching historic highs.

Last year, according to the Governors Highway Safety Association, more than 7,500 pedestrians were killed while walking on U.S. roadways. Between 2010 and 2021, pedestrian deaths rose 77%. This increase has taken us to a 40-year high for pedestrian fatalities.

It should come as no surprise that when cars are given more space, drivers are more likely to speed. One study from the Journal of Accident Analysis and Prevention found roadside factors such as landscaping, houses and sidewalks cued drivers to speeds of around 30 mph, while wider roads with painted lines prompted them to judge the appropriate speed at about 50 mph. On rural roads, people drive slower when lanes are narrower, center lines are double yellow or wide, or when traffic is heavy.

But research also shows that planning decisions that prioritize people over parking results in safer outcomes for pedestrians.

Virginia had 585 pedestrian deaths between 2018 and 2020, according to data from the Smart Growth America “Dangerous by Design” report.

As zoning is visually mapped across the Commonwealth, one hopeful use for the data is strategic local and regional transportation improvements. This type of planning can reduce the dangerous trend of deaths and create the walkable, mixed-use communities more and more Americans wish to see.