The FWD #236 • 664 words

Despite return-to-office mandates making headlines, remote work has settled into a new normal that’s reshaping Virginia’s housing landscape.

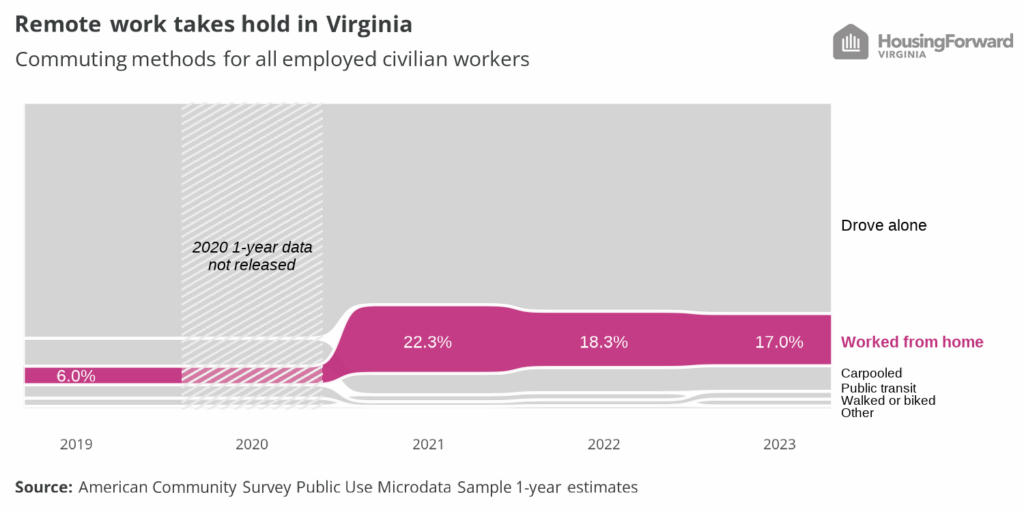

If you’ve been following the news, you might sometimes be led to think the remote work experiment is ending. The data tells a different story, however. At least of as 2023—the most recent year for reliable estimates—remote work in Virginia has stabilized at nearly three times pre-pandemic levels. Today, around 17% of Virginia’s workers uses their home as their primary office. This isn’t a temporary blip; it’s a fundamental restructuring of how and where we work.

The new equilibrium

The dramatic spike to 22.3% remote work in 2021 has mellowed, but we’re nowhere near returning to the old normal. Today’s workplace has crystallized around hybrid arrangements, with most knowledge workers spending 2-3 days in the office. Tuesday through Thursday have become the new rush hours, while Friday offices remain ghost towns at just 32% occupancy.

This pattern persists despite high-profile pushback. Stanford research suggests that even with federal mandates affecting Virginia’s 140,400 federal employees, overall remote work rates will drop by less than half a percentage point. Why? Workers vote with their feet—companies enforcing strict five-day returns face 13% higher turnover, with top performers most likely to leave.

Geography gets scrambled

Remote work hasn’t just changed when we work—it’s fundamentally altered where we choose to live. The traditional jobs-housing balance that once tethered workers to employment centers has loosened considerably.

Northern Virginia tells one side of this story. The region has shed population every year since 2013, a trend that accelerated when remote workers discovered they could keep their six-figure salaries while escaping median home prices that rival Seattle. Metro ridership hovers stubbornly at 50% of pre-pandemic levels.

Rural counties tell the flip side. New Kent, Goochland, Louisa, and Caroline Counties have become magnets for remote workers seeking space and affordability. These areas built twice as many homes in 2021 as in 2016, while Northern Virginia construction actually declined. Winchester emerged as the state’s fastest-growing metro area, fueled primarily by D.C. escapees.

Winners, losers, and the squeezed middle

Federal Reserve economists point to a startling statistic: remote work drove 60% of the pandemic-era 24% housing price surge nationwide. In Virginia, this created clear winners and losers.

Winners include rural communities with good broadband and existing residents who owned homes before 2020. These homeowners captured significant equity gains as remote workers bid up prices.

The losers? Longtime residents in newly “discovered” communities who now find themselves priced out. Charlottesville is one example—wealthy remote workers from Northern Virginia exacerbated a preexisting shift toward housing being more more expensive relative to local incomes. Local workers increasingly commute from surrounding counties they once considered too remote.

Young workers and first-time buyers also face particular challenges. They compete against remote workers importing urban salaries to previously affordable markets, creating 20% premiums for homes with dedicated office space and strong internet connectivity.

Policy tensions mount

Virginia faces a unique policy squeeze. Governor Youngkin’s changes to state telework policy led many state employees to consider jumping over to the private sector. Meanwhile, federal return-to-office mandates put Northern Virginia’s economic engine at risk just as private employers double down on flexibility to attract talent.

This fragmentation creates planning nightmares. How do you invest in transportation when commuting patterns vary wildly by employer? How do you plan housing when a federal policy shift could suddenly return 140,000 workers to daily commuting?

Looking ahead

The office isn’t dead, but neither is it mandatory. Virginia’s housing market must reckon with a permanent shift where roughly one in five workers maintains significant location flexibility. This new reality demands fresh thinking about everything from transit planning to affordable housing strategies.

Communities that recognize and adapt to this shift—investing in broadband, adjusting zoning, and protecting affordability—will thrive. Those waiting for a return to 2019 patterns may find themselves waiting indefinitely.

The chart at the start of this blog shows what Virginia’s workforce already knows: remote work isn’t a pandemic anomaly to be corrected. It’s the new foundation of our economic geography.