The FWD #B09 • 1,316 Words (!)

What is Section 8? The short answer, and the long one.

As far as affordable housing jargon goes, the word that laypeople are most likely to know is “Section 8”. When talking to the general public about government-subsidized housing, it’s often the first term that comes into their minds. But all too frequently, it elicits inaccurate and negative associations.

So what exactly is Section 8, and why is it so important in the ecosystem of affordable housing?

The short answer, we hope, is pretty simple.

Before we start, you should know the phrase “Section 8” is a literal reference to a part of the Congressional Housing and Community Development Act of 1937, one of the first major pieces of housing legislation in the United States. However, it wasn’t until the 1970s that Section 8 of the Act began evolving into what it is today.

Today, Section 8 includes several federal housing programs that provide assistance to low-income renters to help them afford apartments that are privately owned and operated. Homes supported by Section 8 are not developed, owned, or operated by the government.

Most Section 8 assistance today goes to Housing Choice Vouchers (HCV), which help recipients find and pay for housing on the open market that would otherwise be out of reach. If applicants are accepted, chosen, and subsequently locate a home using the voucher, their local housing authority begins paying their landlord or mortgage loan servicer directly. (Yes, vouchers can be used by homeowners as well as renters!)

Although the HCV process seems straightforward in practice, decades of discrimination and a backlog of voucher requests have prevented many low-income Americans from utilizing vouchers to secure stable housing.

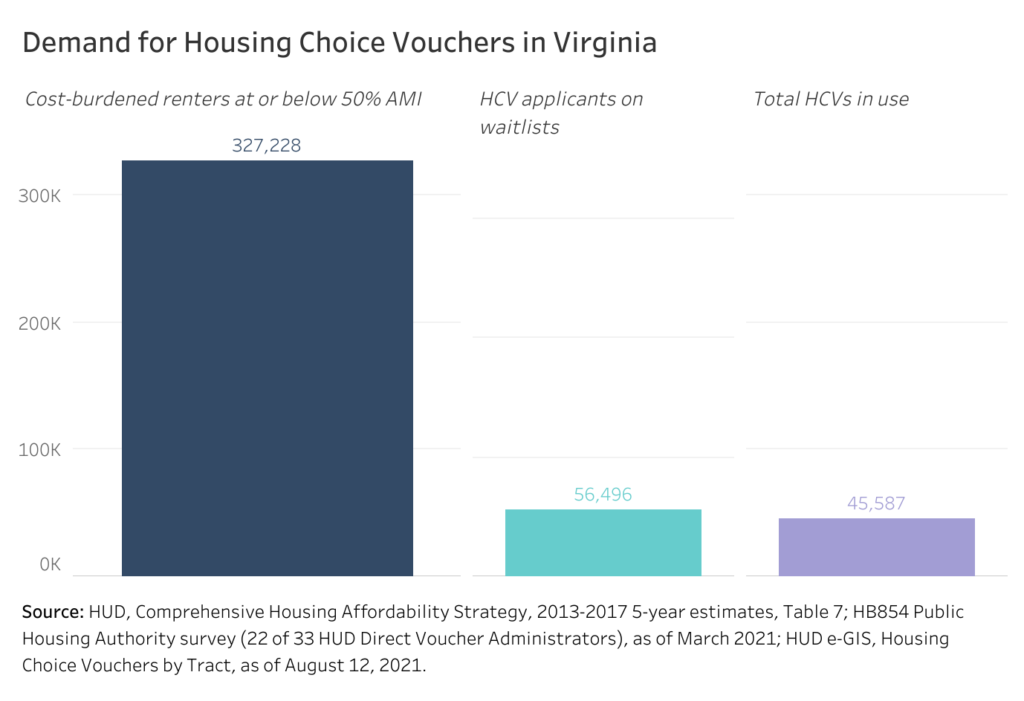

In Virginia, vouchers help tens of thousands of renters in Virginia afford their homes.

According to the latest data from HUD’s Housing Choice Voucher dashboard, 48,300 Virginians use HCVs to afford their apartment and enjoy housing stability. Depending on the region, this still only amounts to roughly one in ten eligible households.

HUD’s dashboard also currently shows around 5,300 Project-Based Vouchers being used across the state. This is about 11% of all HCVs in use.

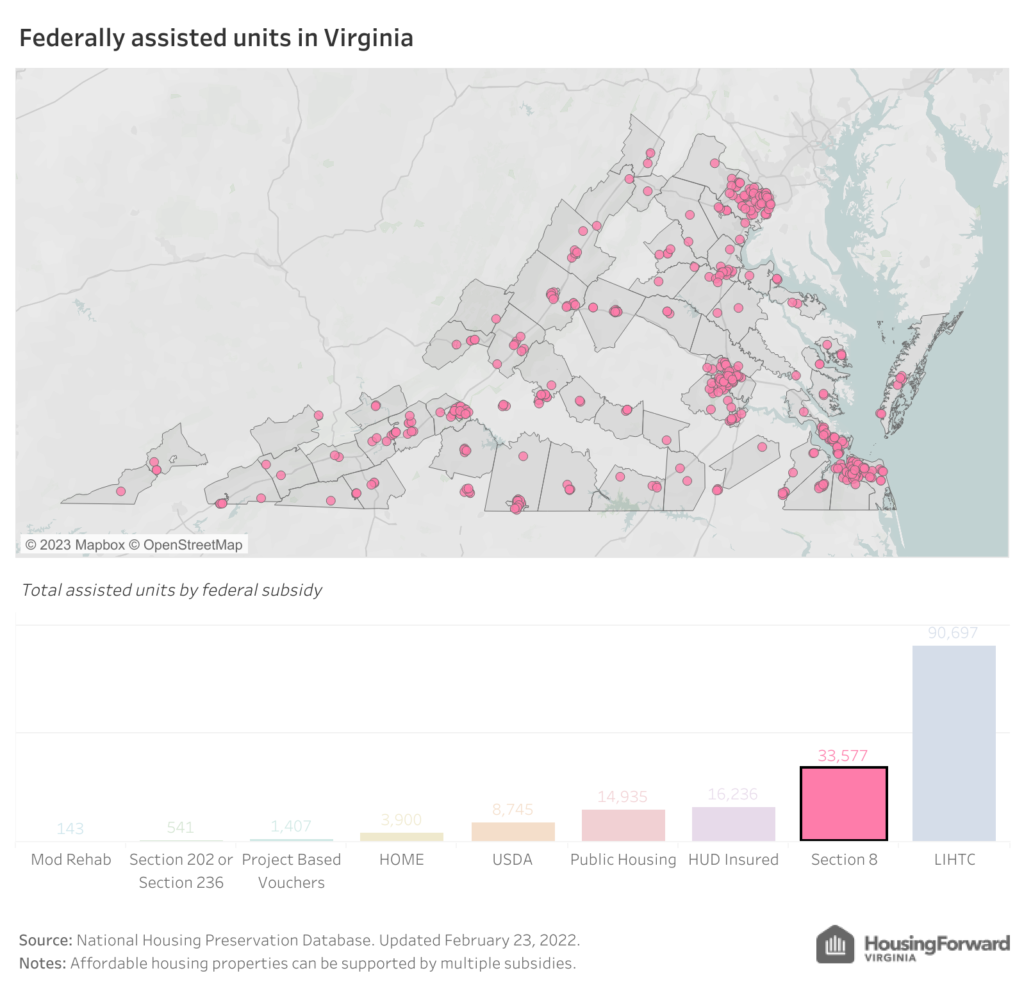

As of 2022, Virginia still has around 33,600 units supported by “old school” Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance contracts. These are found throughout all parts of the state, including many in rural communities.

The long answer is a little more complicated.

“Section 8” as we know it today began in 1970 when congress directed HUD to experiment with giving out allowances for housing payments. Originally the tenant would pay 15-25%, and the housing authority would pay the rest. The tenant’s share was later increased to 30%.

Then, in 1974, a new program was introduced called Project-Based Rental Assistance (PBRA). This was called “Section 8 New.” Under PBRA, a housing authority would enter into 20-40 year contracts with private owners to offer their units to voucher holders. In 1983, congress repealed the authorization for new PBRA contracts and introduced the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) to take its place.

The modern Housing Choice Voucher program was finally introduced in 1987. Voucher holders would be free to rent at any price, but the value of their voucher would be based on their income and the HUD-calculated Fair Market Rent. The vouchers would also be portable across cities and even states. Finally in 1998, tweaks were made to the legislation and “Project-Based Vouchers” (PBVs) were introduced. Project-Based Vouchers are part of a housing authority’s total HCV allocation, and the authority can choose how many HCVs they want to “project base.”

“Vouchers” can mean two different things.

One common misconception about Section 8 is that it is one program. In reality, the housing voucher program is really two programs authorized under the same law, administering different types of vouchers:

- A project-based voucher is tied to a specific unit or building. The unit/building is subsidized, regardless if anyone moves in or out; in other words, tenants lose their subsidy if they move out of a project based unit. The landlord contracts with the state or local housing authority to rent the unit to low-income households.

- A tenant-based voucher is tied to a voucher-holder who is free to select any housing unit. Low-income households with these vouchers can use them to pay for any home that meets program guidelines; in other words, the voucher follows them across units. This is the most common form of Section 8 voucher.

All together, project-based vouchers support nearly 2 million individuals across the country, while another 5 million are helped by tenant-based vouchers.

What does low-income really mean?

Using the median family income as the “Area Median Income” (AMI), HUD produces income limits for 30, 50, and 80 percent of AMI, further broken down by number of persons within a household. These levels correspond to common terms to describe these income ranges:

- Between 80 and 50 percent AMI is low-income,

- Between 50 and 30 percent AMI is very low-income, and

- Below 30 percent AMI is extremely low-income.

Check out Sourcebook to find your locality’s AMI limits.

So how does the math work?

A voucher recipient’s monthly housing cost is partially or fully covered by the voucher. Each household will only spend approximately 30% of their income on rent, and the specific dollar amount provided to landlords is primarily dependent on the income of the voucher holder. Let’s look at a simplified example, where a single person in Virginia Beach making around $20,000 a year is looking to determine their voucher amount.

Total Rent Owed* = $1,380

Tenant Fair Portion of Monthly Rent based on Income** = $500

Section 8 Subsidy: $1,380 – $ 500 = $880 monthly voucher

*(Based on median gross rent in Virginia Beach)

**(30% of $20,000 is $6,000 annually, or $500 monthly) Other factors are also considered when determining a household’s eligibility and fair portion of the rent, including medical debt, and number of dependents or children.

How are HCVs administered in Virginia?

Most HCVs are allocated from HUD directly to local housing authorities, which are mainly in urban areas. Virginia Housing also gets about 9,000 HCVs for itself, which it allocates through 31 local agencies in 80 cities and counties across the state in mostly rural areas.

What are the challenges?

Vouchers are effective ways for local housing authorities to ensure that low-income households have access to a diverse range of quality housing. In theory, these vouchers would allow families to live comfortably in the areas closest to their jobs, schools, and essential services. In reality however, vouchers can come with challenges that continue to plague their users.

Demand exceeds available assistance. More than 56,000 households are on HCV waiting lists across the state, and an estimated 327,000 eligible low-income renters are cost-burdened and in need of housing assistance.

Voucher holders still face problems finding a good home. Virginia law did not protect HCV holders from discrimination by landlords until recently, when source of funds was added to the state’s Fair Housing law as a protected class.

Many aging Section 8 properties need to be preserved. According to data from the National Housing Preservation Database, over 1,700 units in Virginia are expiring in just the next five years alone.

Complicated or not, Section 8 continues to be relevant.

However you may hear it being referred to—Section 8 or the Housing Choice Voucher Program— government subsidized housing remains more important than ever. As the Commonwealth and the nation at large continue to witness the financial impacts of COVID upon our lowest-income residents, the demand for rental assistance will continue to persist. Understanding how vouchers work and what challenges they face are crucial in the long-term realization of truly affordable and equitable housing for all Virginians.