The FWD #204 • 995 Words

A new Connecticut law sets affordable housing construction goals for localities.

The 2023 Connecticut General Assembly Session wasn’t the first time a Fair Share Planning and Zoning bill was introduced. Bipartisan opposition scuttled it twice before, but the third time was the charm for advocates. Senate Bill 998 finally brought “fair share” housing to The Nutmeg State.

The bill requires the Secretary of the Office of Policy Management, along with a panel of advisors, to determine the total number of new affordable units needed in Connecticut. Then, the group will follow certain guidelines outlined in the bill to develop a methodology for allocating a “fair share” obligation to each municipality.

For example, the bill exempts fair share requirements for communities with poverty rates above 20%. Any “shares” assigned to those areas must be redistributed to higher opportunity municipalities. In theory, this mechanism will help even more lower-cost homes get built in historically exclusionary communities.

The Secretary and advisory group have until December 1, 2024 to calculate the housing need and develop the allocation methodology. However, opponents aren’t waiting for specific mandates to lament the bill’s adoption. Detractors argue that legislators failed to adequately engage local communities, and that the new measures will unjustly strip municipalities of their land use controls.

It’s not a new idea. In New Jersey, fair share housing has been the law of the land for half a century.

Mount Laurel, a New Jersey township about half an hour’s drive east of Philadelphia, became a popular destination for white families leaving the city in search of more racially homogeneous neighborhoods in the 1960s. By 1970, the township’s population had more than doubled. This white flight quickly upended the lives of Mount Laurel’s small community of Black residents, many of whom lived in homes passed down for several generations.

As white families competed for a limited supply of homes, their greater wealth began to methodically price out Black families. The Township Council, after white residents gained its control, enshrined exclusionary zoning practices to also prevent the construction of moderately priced apartments and homes. The township went even further by condemning and demolishing the homes of residents that could no longer afford to live there.

To combat these exclusionary practices, in 1969 Black neighbors organized and pooled enough resources to develop 36 new affordable homes. Modest rents for the garden-style apartments would be supported by new federal subsidy programs created by the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965.

But there was a catch. Before construction could begin, the project required zoning approval. Mount Laurel’s zoning board swiftly denied the application. After the decision, Mayor Bill Haines infamously quipped, “If you people can’t afford to live in our town, then you’ll just have to leave.”

Refusing to back down, community organizers filed a class action lawsuit against the township with the help of the local NAACP chapter. The suit claimed that Mount Laurel’s zoning laws purposefully excluded residents from living in the township based on race and class. As the case proceeded through trial and appellate courts, other affordable housing developers and advocacy groups joined as plaintiffs.

Finally, in 1975, the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled against the township and held that all municipalities in the state must provide their “fair share” of affordable housing. This landmark decision—the Mount Laurel Doctrine—established a legal framework that would be challenged, tweaked, and enhanced throughout the coming decades.

A significant change came in 2015, after the nonprofit Fair Share Housing Center (FSHC)—a watchdog group established in the wake of the 1975 decision—sued the New Jersey Council on Affordable Housing (COAH). State lawmakers created COAH in the 1980s as an independent agency responsible for enforcing the Mount Laurel Doctrine, but it had perpetually shirked its legal responsibility to adopt and promulgate updated regulations since 1999.

Once again, the New Jersey Supreme Court defended fair share housing and delegated enforcement of the Mount Laurel Doctrine back to state courts. Furthermore, municipalities are obligated to work with FSHC and other stakeholders to meet their fair share of affordable housing.

The 2015 decision created a unique foundation to counteract exclusionary zoning.

The Mount Laurel Doctrine (in conjunction with New Jersey’s Fair Housing Act) uses a formula to determine the fair share of affordable housing each municipality must build. Higher or lower requirements are based on three factors: 1) recent job growth, 2) existing affordability, and 3) vacant, developable land in targeted growth areas near major transportation corridors and job centers.

This legal obligation also seeks long-term affordability through deed restrictions. In nearly all cases, homes remain affordable for at least 30 years. The framework includes consequences for noncompliance, including the ability to reverse zoning decisions under threat of litigation. FSHC and other advocacy organizations continue to monitor compliance and promote enforcement.

Do fair share obligations actually create housing?

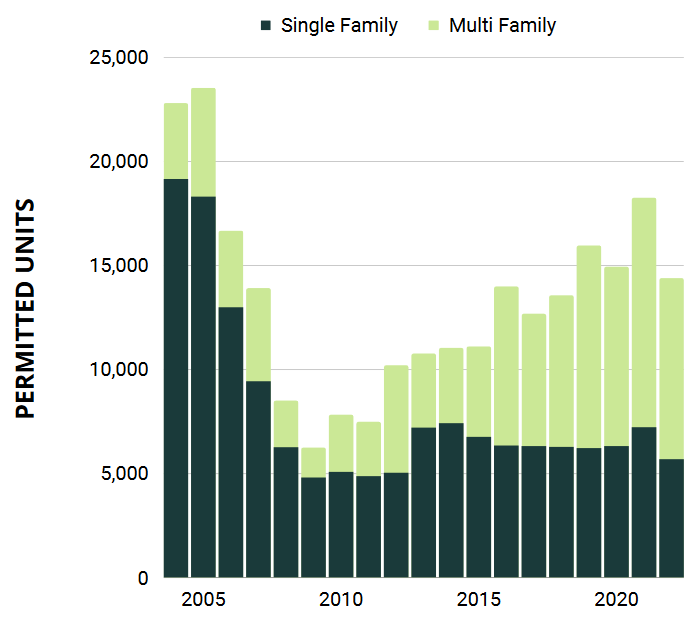

A recent FSHC report compared residential development trends since 2015 to previous completions, dating back to 1980. FSHC found that the average number of new homes produced each year had increased by 86%, and that 81% of new multifamily developments—nearly 70,000 apartments—were a direct result of the fair share obligation.

Furthermore, stronger enforcement since 2015 led to 21,891 new deed-restricted affordable units over just seven years. By comparison, roughly 50,000 had been produced in the 34 years prior. The pace of new affordable housing deliveries in New Jersey has now more than doubled.

While these findings are strong evidence for the effectiveness of fair share housing, the policy hasn’t proliferated outside of the Garden State yet. Even then, the stronger enforcement mechanisms apparently responsible for recent successes have, for the most part, existed during some historically remarkable market conditions that complicate causality.

More research is needed to thoroughly assess fair share housing, especially to examine its effects on racial equity and housing affordability for low-income residents. However, with Connecticut now on board, we’ll be sure to watch closely and share the results of this rare experiment in housing policy.