The FWD #191 • 1,018 Words

School may be out, but we’re doing our homework to bring you noteworthy findings from housing research published this year.

Believe it or not, choosing a topic for each of our blogs is one of the hardest jobs we have. So this week, we’re embracing indecision and featuring a collection of notable housing studies from the first half of 2023. As you’ll see, many of these findings are very relevant to ongoing conversations about affordability, land use, and equitable housing policy throughout the Commonwealth.

What actually happens when we upzone?

Zoning Change: Upzonings, Downzonings, and Their Impacts on Residential Construction, Housing Costs, and Neighborhood Demographics (April 2023)

A growing chorus of advocates continues to press local governments to increase allowable densities (“upzone”) in areas with high housing demand. Let the market add supply more easily and quickly, the argument goes, and prices will stabilize as demand is met.

It’s a sound theory, but does empirical evidence back the claim? According to an April study from the Urban Institute’s Yonah Freemark, it’s complicated. Freemark assessed findings from every relevant article published in recent years evaluating the impacts of upzoning and downzoning to build the first comprehensive review of this research.

Reducing allowable densities, apparently, does what you’d probably expect: construction opportunities are limited, prices go up, and existing patterns of segregation are reinforced. Upzoning, however, has “varying short and long-term effects” according to Freemark’s Twitter summary of his major findings.

Notably, studies seem to show counterproductive effects immediately following new construction. New homes are almost always more expensive relative to their surroundings (unless otherwise subsidized), so prices on average can increase and limit economic integration.

But the opposite appears true when effects are evaluated on a longer scale and at the regional level. Signs point to new development reducing prices over time across metros. Likewise, some research points to diversity increasing in regions that upzone more than others.

Unraveling the many direct and indirect causal chains here will clearly take more work. But this synthesis is a very useful starting point, especially for teeing up the dynamic between community versus region-wide benefits.

How does new construction impact low-income communities?

Local Effects of Large New Apartment Buildings in Low-Income Areas (March 2023)

New market-rate development in lower-income neighborhoods is often contentious. Residents have reasonable concerns about accelerating rents, demographic changes, and potential displacement. Unlike the study above, this research investigates actual housing production (rather than just changes in local land use) and is focused only on neighborhoods with below-average incomes.

Looking at microdata across eleven major U.S. cities, the authors looked at buildings finished in 2015 and 2016 and tracked rents from 2013 to 2018. They found that new apartments can actually reduce nearby rents around 6%, relative to areas further away or developed later. Furthermore, the added supply can facilitate increases in new residents into those neighborhoods from other low-income areas.

So what’s going on here? The authors suggest that “endogenous amenity” effects increasing demand (such as higher-end retail and services) are offset by new units to absorb higher-income residents moving into the community. Residential development follows neighborhood changes already underway, not the other way around.

Therefore, the evidence does not point to new construction as a primary catalyst for local rent increases in lower-income neighborhoods. In fact, enough new supply can actually reverse rising rents.

Buy-to-rent lessons from The Netherlands

Buy-to-Live vs. Buy-to-Let: The Impact of Real Estate Investors on Housing Costs and Neighborhoods (June 2023)

Last year, in response to growing concerns over “buy-to-let” purchases, the Dutch government passed a law granting localities the power to ban investors from buying and leasing out homes. The City of Rotterdam quickly adopted such a ban in an attempt to preserve the supply of lower-cost homes available for prospective homebuyers. The ban applied only to a subset of neighborhoods.

To determine the effects of this new policy, researchers collaborated with the city to track impacts on purchase activity and housing prices. Unsurprisingly, the ban worked. The share of owner-occupied homes purchased and leased out by investors (relative to all sales) dropped 23% citywide.

However, achieving this goal came with several side effects, which one author explains in a Twitter thread. First, reducing investor activity did not have a significant impact on overall home sales prices. Rents, on the other hand, rose 4% where the ban applied, compared to other areas of the city.

The ban also changed the composition of new residents. Compared to buy-to-let tenants, new homebuyers in these neighborhoods tended to have higher incomes, were much older, and were more likely to be an existing Dutch resident rather than a recent immigrant.

New perspectives on the power of LIHTC

LIHTC Provides Much-Needed Affordable Housing, But Not Enough to Address Today’s Market Demands (July 2023)

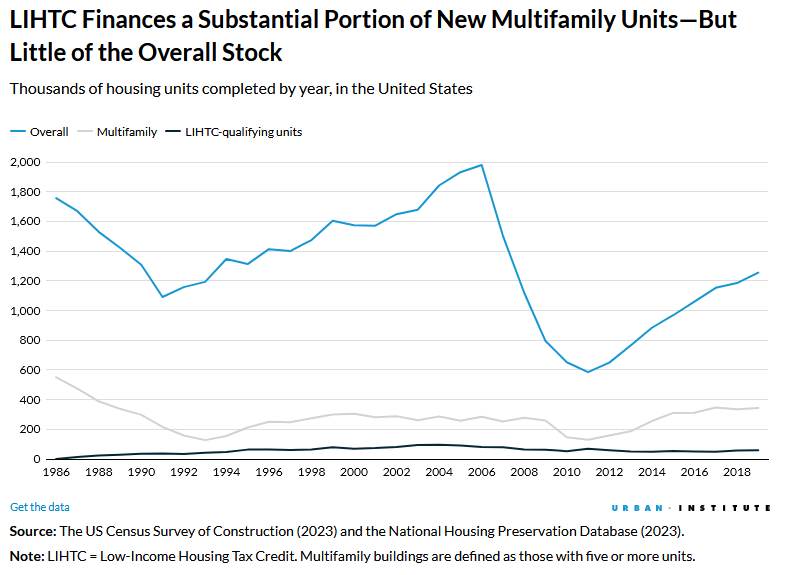

To close us out today, we’ll look at another recent investigation by the Urban Institute, this time on the surprising impact of Low-Income Housing Tax Credit investments over the past two decades.

Blending LIHTC property data from the National Housing Preservation Database with total multifamily production statistics, they discovered that one in four of all new apartments built across the country from 2000 to 2019 were attributable to LIHTC development. And yes, only new construction LIHTC projects are included—no rehabs or acquisitions of existing units.

Here in Virginia that share happened to be significantly lower—just 17%—likely due to steady market-rate additions to apartment supply in Northern Virginia. On the other hand, some rural states had LIHTC to thank for more than a third of all new apartments. In Mississippi, for example, LIHTC produced just over half (51%) of its multifamily stock over that twenty year period.

As the pace of multifamily production continues to pick up, LIHTC’s share of new apartment stock has steadily declined over recent years. But LIHTC allocations are growing, too. In 2019, just over 50,000 new LIHTC units were placed in service; in 2021, credits were awarded to 90,000 new units across the country. Still, the authors note how this increase remains well below levels actually needed to meet the affordable housing needs of American renters.