Zoning in Virginia Today

One of the most comprehensive resources for land use and zoning in Virginia is the Albemarle County Land Use Law Handbook. Authored by former County Attorney Greg Kamptner, the Handbook is the most in-depth survey of Virginia’s planning, zoning, and subdivision laws, and was regularly updated until Kamptner’s recent retirement.

This section of the toolkit pulls heavily from the Handbook. For more detailed information, we highly recommend reading the Handbook section relevant to your questions.

Enabling Legislation

Zoning is one of the most important tools local governments have. As Virginia is a Dillon’s Rule state—where localities only have powers that are specifically granted to them by the state legislature—Virginia localities have the power to create zoning districts under Virginia Code § 15.2-2280.

According to that section of the Code of Virginia, the purpose of zoning is “to promote the health, safety, morals, and general welfare of the community, to protect and conserve the value of buildings, and encourage the most appropriate use of the land.”

To achieve these objectives, the Code even lays out what should be considered when crafting zoning regulations (Virginia Code § 15.2-2283) and making zoning decisions (Va. Code § 15.2-2284).

What kind of powers do localities have over housing?

Through zoning, localities have the power to regulate, restrict, permit, and prohibit aspects of land, water, airspace, buildings, and structures within their boundaries. This gives localities broad power to determine what their communities can look like and what types of housing can be built.

Localities can use zoning to control:

- USES: The general use of land, buildings, structures, and other premises for agricultural, business, industrial, residential, flood plain, and other purposes. Localities wield this power to reserve land for particular uses, like housing.

- PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF STRUCTURES: The size, height, area, bulk, location, erection, construction, reconstruction, alteration, repair, maintenance, razing, or removal of structures. With this power, localities can set things like height limits and minimum square footage requirements.

- AREAS OF USE: The specific areas and dimensions of land, water, and air space to be occupied by buildings, structures, and uses. This can encompass open spaces to be left unoccupied, like parks, or specific rules related to the size and shape of lots. This most often takes the form of minimum lot size requirements (e.g., a lot for a single-family home cannot be smaller than 1 acre).

What can’t localities do with housing?

§ 15.2-2288.1. Localities may not require a special use permit for certain residential uses. This section of the code prevents a local government from requiring a Special or Conditional Use Permit for any residential development that is allowed by right in the zoning code. Basically, if it’s by right, then it’s by right—no entitlement process required.

§ 15.2-2290. Uniform regulations for manufactured housing. This statute requires that local governments allow manufactured homes (also known as mobile homes) in their agricultural zoning districts. It also allows localities to establish uniform building standards for housing in agricultural zones, as long as they apply evenly to all types of housing and do not single out manufactured housing.

§ 15.2-2291. Assisted living facilities and group homes of eight or fewer; single-family residence. This section mandates that any assisted living facility for elderly or disabled people with eight or fewer residents should be considered single-family homes for the purposes of zoning. Essentially, this allows small assisted living and group homes in otherwise single-family-only zones.

§ 15.2-2286.1. Provisions for clustering of single-family dwellings so as to preserve open space. This section explicitly allows “cluster developments” in residential and agricultural zones, and prevents a locality from excluding the conserved open space from the density calculation. A cluster development is a housing development that concentrates all its units in a small area of the parcel while maintaining the rest of the parcel as open space. By including the open space in the density calculation, the effective density is typically much lower, and so is more likely to be allowed by right in a low-density residential or agricultural area.

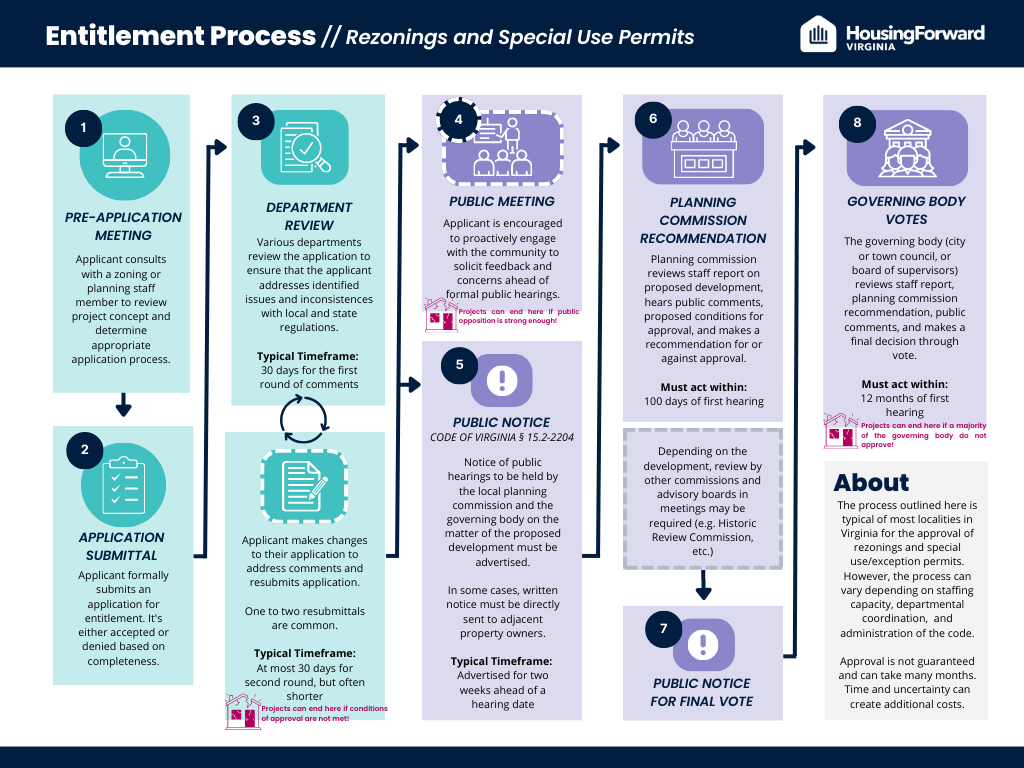

The Entitlement Process

When a certain land use or development pattern isn’t allowed by right, developers need to get legal approval to develop or redevelop their property in that way. This is called the entitlement process. Once received, entitlements give owners a vested right to develop that property that cannot be taken away.

Wait, what does “by right” mean? By-right development means that the proposed development conforms to existing zoning and building codes, so it doesn’t require any special consideration for approval.

For localities, the entitlement process provides a level of review and oversight to make sure developments are compatible with the community and meet the goals of their Comprehensive Plan.

This process involves a locality’s planning department, planning commission, governing body (city/town council or board of supervisors), and community members.

Types of entitlements

There are three types of entitlements. Which entitlement a property owner or developer pursues depends on how the proposed development diverges from existing zoning rules.

- REZONINGS are pursued when a proposed development is not permitted by right and another zoning classification is desired so its designation matches its intended use. Example: A developer buys a derelict industrial building close to downtown, with the intention of demolishing it and building a shiny new high-rise apartment tower with a restaurant on the ground floor. The industrial zoning district doesn’t allow those uses, so the developer seeks to have the parcel rezoned for downtown, high-density, mixed use.

- SPECIAL USE PERMITS (SUP) are pursued when a proposed development use is not permitted by right but may be appropriate and compatible with the existing built environment. SUPs are often required when the proposed use may have external effects on the surrounding neighborhood, including traffic, noise, and light. SUPs do not change the property’s zoning—they grant an exception to the rule. Example: you buy a home in a city neighborhood and want to convert the ground floor to a coffee shop. That use isn’t allowed in the residential-only zone the home resides in, but a coffee shop would fit into the neighborhood nicely. In this case, you would seek an SUP to allow the coffee shop.

- CONDITIONAL USE PERMITS (CUP) are used interchangeably with SUPs.

- VARIANCES and SPECIAL EXCEPTIONS are pursued when a proposed development deviates from aspects of a locality’s zoning ordinance and strict adherence to the ordinance would create unnecessary hardship for the property owner. Most often, this occurs due to unusual physical characteristics of a lot. For example, building an 800-square-foot home in a zoning district where the minimum square footage required is 1,000 square feet would require a variance.

Virginia State Code requires that both rezonings and SUPs go through a series of advertised public hearings with the planning commission and governing body. Variances are required to be heard by the Board of Zoning Appeals (BZA) and meet certain public hearing requirements, like mailings to adjacent property owners.

How does the entitlement process impact housing?

For builders and developers, the entitlement process adds uncertainty to projects. It increases the time to develop housing and can sometimes stop projects in their tracks—especially if community members oppose a project. Often, in the context of public hearings, the loudest voices in the room are those that are saying “Not In My Backyard” (NIMBY). These voices can belong to anybody and can give any number of reasons to oppose new housing, or any other land use for that matter. However, NIMBY is most often attributed to homeowners opposing denser, more affordable housing.

Did you know?

An early recorded instance of the word “NIMBY” appeared in Newport News’ Daily Press in June 1980. It was referring to opposition to a proposed nuclear waste disposal facility in Virginia; apparently the word was already common within the hazardous waste industry. Maybe treating low-income households like environmental pollutants has a deeper history than we thought.

In theory and often in practice, homeowners have a material interest in restricting the supply of housing. All else being equal, the fewer homes are available, the faster the value of existing homes increases, which leads to greater equity for homeowners. Of course, in real life, there is no evidence that new development decreases home values, and in fact some studies find it can have a positive effect. But this simple supply and demand theory can be a powerful motivation for NIMBY homeowners.

As well, people who own homes have been found to be statistically more likely to participate in local government. This all means that the NIMBY opposition tends to have a larger and more organized presence than any pro-housing “YIMBY” contingent.

Aside from any public opposition a project might encounter, the entitlement process is often factored into the cost of development. Red tape can increase timelines and, in turn, increase costs as building material costs rise and funding opportunities slip away.

Understanding the connection between proffers, zoning, and affordable housing

As part of the entitlement process, Virginia localities typically request developers to contribute public benefits, known as proffers, to help mitigate the impact of any development requiring a rezoning or SUP, residential or not. For housing developments, many localities have adopted formulas, known as proffer guidelines, which determine the value and type of proffers expected based on the number of dwellings the rezoning or SUP allows. These proffers can take many forms: utility upgrades, public street or sidewalk improvements, planting trees, or even cash payments to the government

In 2016, the General Assembly passed legislation that created guidelines on what is considered reasonable or unreasonable for proffer requests. According to the legislation, proffers are reasonable only if they address an impact that can be directly tied to a new residential development (e.g. an apartment building) or a new residential use (e.g. rental housing). This legislation essentially prohibited localities from suggesting, requesting, or accepting an unreasonable proffer.

Many localities reacted to this legislation by pausing rezoning applications and repealing their local proffer policies, which included cash proffer guidelines that were now in violation of the new law. This legislation was seen by many as effectively stripping local governments’ ability to negotiate with developers. If a developer felt that a proffer condition was unreasonable, they could take a locality to court for violating state law.

Reactions to the 2016 legislation led Delegate Bob Thomas to introduce HB 2342 during the 2019 General Assembly session in the House, with Senator Barbara Favola following with SB 1373 in the Senate. HB 2342/ SB 1373 passed in both houses and made significant amendments to the 2016 legislation, including:

- Localities are only prevented from requiring in writing an unreasonable proffer;

- Applicants for rezoning can submit any on- or off-site proffers that they themselves have deemed reasonable and appropriate;

- Verbal discussions cannot be used as a basis for determining that an unreasonable proffer or proffer condition amendment was required by the locality.