The Origins of Zoning in America

Zoning isn’t all that old. Most cities founded before the industrial revolution were well-developed even before the advent of zoning. In North America, zoning has largely focused on limiting areas to a single land use (i.e. agricultural), while mixed-use zoning dominates in many other nations.

Let’s take a look at some of the major events that led to the current system of American zoning.

1904

Los Angeles passes the first zoning ordinance. This first municipal zoning ordinance didn’t cover the whole city, it simply created three residential-only zones where laundries and wash-houses were prohibited. Laundries and wash-houses tended to be owned by Chinese immigrant families at the time, and these zones were likely intended to keep Chinese immigrants out of white neighborhoods. In 1908, another ordinance created six industrial zones and designated all non-industrial land as residential.

1910

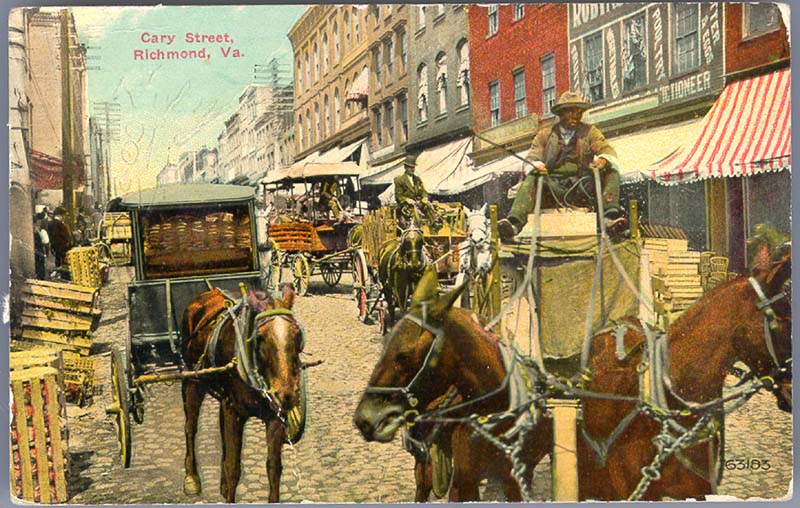

Explicitly race-based zoning ordinances are passed. Baltimore was among the first cities to formally segregate its residential zones by race. Many other cities followed suit, including Richmond, Atlanta, New Orleans, St. Louis, Oklahoma City, and Louisville.

What is race-based zoning?

Race-based zoning (also known as racial zoning or segregation zoning) is the creation of zoning regulations or policies that explicitly segregate residential areas based on racial or ethnic criteria.

This discriminatory approach sought to separate people of different races or ethnicities into distinct geographical areas, limiting their access to certain neighborhoods or communities based. The Supreme Court declared race-based zoning unconstitutional in 1917, but exclusionary practices continued to promote segregation in other ways.

Check out our toolkit, Racial Equity in Virginia, for more information on how a long history of exclusionary policies and practices created unequal housing opportunities in Virginia.

1916

New York City passes the first city-wide zoning ordinance. The 1916 Zoning Resolution created land use zones for the entire city. It also restricted the height and shape of buildings to ensure light and air could reach the streets. Not only did this create the iconic stepped-back look of many of New York’s most famous skyscrapers—it also became the basis for many more cities’ first zoning laws.

1917

The U.S. Supreme Court strikes down racial zoning in Buchanan v. Warley. In 1915, a lawyer for the NAACP named William Warley offered to buy a piece of land in a white-only neighborhood in Louisville from a white man named Charles Buchanan. Warley’s only condition was that he would only buy it if he, a Black man, could legally occupy the property.

When Warley did not complete the sale, Buchanan sued him. Buchanan argued that the race-based zoning ordinance preventing Warley from occupying the land was unconstitutional, so the sale should continue. The Supreme Court sided unanimously with Buchanan and struck down all racial zoning under the Fourteenth Amendment. However, some cities continued the practice of racial zoning for decades after the decision, including Norfolk.

1922

The U.S. Department of Commerce releases a draft of the Standard State Zoning Enabling Act (SZEA). This document provided a blueprint for state governments to use in granting zoning powers to localities. It stemmed from an initiative by then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover to increase homeownership in the U.S. The final document was published in 1924, then revised again in 1926.

1926

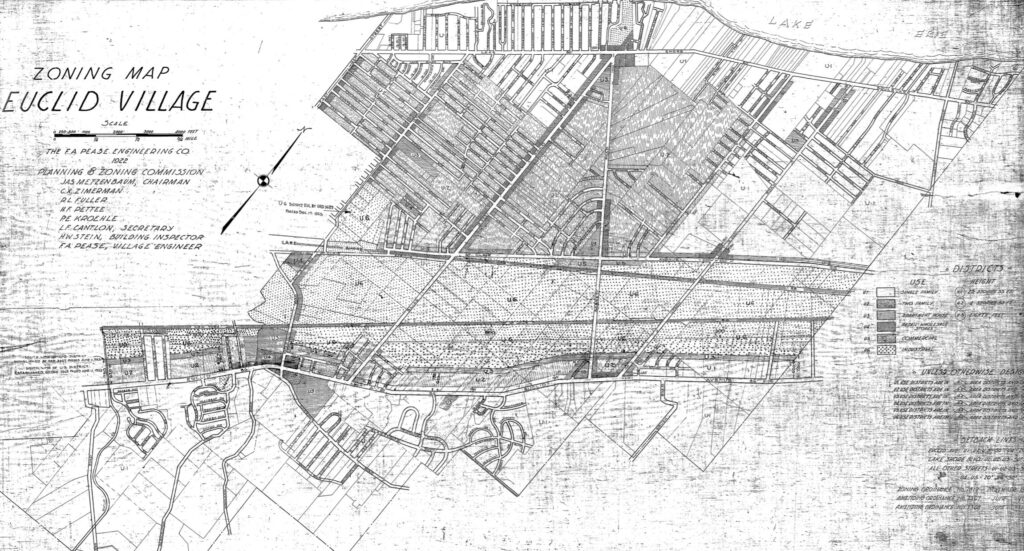

The Euclid v. Ambler decision upholds localities’ power to regulate land use. The Village of Euclid, Ohio had adopted a zoning ordinance to prevent the nearby city of Cleveland from subsuming it as the city grew. Ambler Realty Company owned 68 acres of land in the village. The company had intended to use the land for industrial development, but the zoning prevented it.

Ambler sued the Village, arguing that land use restrictions infringed on liberty and property rights without due process, in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. The U.S. Supreme Court decided in favor of the Village of Euclid. It set the precedent that localities could regulate land use under the police power of general welfare. This is why use-based zoning is known as “Euclidean” zoning.

Zoning History in Virginia

This section draws heavily on McGuireWoods’ report, Zoning and Segregation in Virginia (Part 1, Part 2).

In Virginia, racial zoning was used to segregate cities in the early 20th century, even before formal land use zoning.

In 1911, the city of Richmond used its charter powers to adopt the first ordinance dividing the city into separate blocks for white and “colored” residents. Eleven months later, the General Assembly approved legislation that allowed all cities and towns in Virginia to segregate districts, dividing blocks between white persons and “colored” persons.

Norfolk, Ashland, Roanoke, Portsmouth and Falls Church adopted similar residential segregation statutes, following Richmond’s lead. This predated the first land use zoning laws in Virginia by over a decade. Richmond and other cities’ racial zoning codes were upheld by the Virginia Supreme Court in the 1915 Hopkins v. City of Richmond decision.

After the U.S. Supreme Court struck down racial zoning in Buchanan v. Warley, cities continued the practice for decades. Norfolk notably used “block zoning” to prevent people of color from occupying white city blocks and vice versa. This was accomplished by legally preventing white homeowners from selling to Black buyers or Black homeowners selling to whites, which was considered to still be permissible under Buchanan.

In 1922, the General Assembly passed its first zoning enabling statute, extending the power to regulate land use to independent cities. It was later amended to apply to incorporated towns and areas of lower population density as well.

While Buchanan prevented race from being written into zoning codes, cities were still allowed to consider race in the planning process. This led to cities such as Alexandria zoning swaths of residential land for industrial use simply because a significant number of Black people lived there.

Meanwhile, residential-only zones protected white neighborhoods from polluting industries and prioritized single-family detached housing on large lots. These rules made the homes more expensive, keeping poorer households of color concentrated in higher-density commercial and industrial areas.

After Congress passed the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the first inclusionary zoning policies were introduced in Fairfax County and Montgomery County, Maryland. In Virginia, these policies were explicitly enabled in 1989 when the General Assembly passed a revision to the zoning enabling statute that allowed for inclusionary zoning (called Affordable Housing Dwelling Unit, ADU or AHDU ordinances) in six localities:

- Albemarle County

- Arlington County

- Fairfax County

- Loudoun County

- Alexandria City

- Fairfax City

This gave the localities broad powers to craft local inclusionary zoning ordinances, as long as they gave incentives to developers.

Later legislation extended very limited inclusionary zoning powers to all other localities. In 2020, HB 1101 granted more freedom and clarity to localities in adopting inclusionary zoning ordinances. This included the ability to require affordable unit set-asides when granting Special Use Permits.

For more information on inclusionary zoning history and basic concepts, check out our blog “Back to Basics: Inclusionary Zoning.”