The FWD #190 • 908 Words

Behind the economic theory that advocates tout as the solution to sluggish urban development.

Land Value Tax (LVT) has long been a topic of discussion in economic and policy-making circles. As a departure from traditional improvements-based property taxes, it has been hailed as a remedy for economic disparity but also criticized as a potential obstacle to development. This post will explore LVT, its proponents and opponents, and its progress in various regions of the United States, notably in Virginia, Michigan, California, and New York.

It’s a tax on land—but not on buildings.

Unlike standard property taxes, which consider the value of buildings and other improvements, LVT only considers the value of the land. In theory, LVT encourages owners to optimize the use of their land to offset the tax burden instead of letting it sit vacant or underused. The concept of Land Value Tax (LVT) has its roots in the economic philosophies of the 18th and 19th Centuries. It was brought to the mainstream through the writings and advocacy of the American political economist Henry George, who gave his name to the Georgist school of economic thought.

What are the pros and cons?

Proponents of LVT contend that it presents a financially effective form of taxation, capable of addressing issues such as urban sprawl, housing shortages, and wealth inequality. Given land is an immobile asset with a fixed supply, its taxation doesn’t hinder production, making LVT a distortion-free tax. Georgists argue that this incentivizes owners to develop their land to its highest and best use.

Critics, however, express concerns that LVT could dissuade property ownership and potentially destabilize real estate markets. They argue that it might unfairly burden landowners who purchased land as a long-term investment for future use. Opponents also cite practical challenges related to accurately assessing land value, separate from improvements.

George’s ideas on LVT have been influential, and several communities and cities in different parts of the world have experimented with LVT at different times in history. However, it’s worth noting that a pure version of George’s proposal—a tax on land values that completely replaces all other property taxes—has never been fully implemented.

Where does LVT stand today?

In May, The Schalkenbach Foundation hosted an online event called Driving the Shift, a forum to hear about local efforts to advance land value tax policies in places throughout the U.S. Four speakers presented examples and perspectives on this issue.

Michigan:

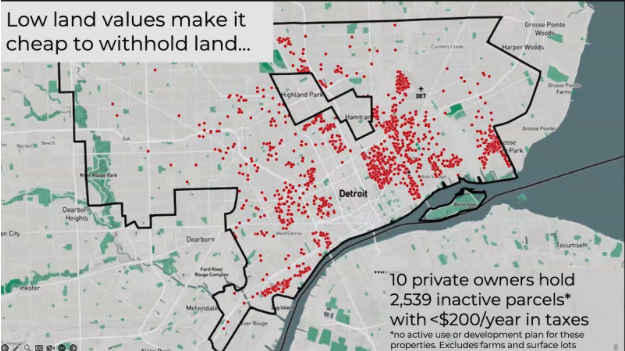

- Nick Allen, a PhD candidate at MIT who co-authored the report Split Rate Taxation in Detroit: Findings and Recommendations and has been helping the City of Detroit design a potential land value tax shift. Supporters, mainly those concerned with long-term tax erosion and city value destruction, see LVT as a tool for revitalization.

What is Split-Rate Taxation and How is it Different from LVT?

While both systems share a common goal, the primary difference lies in their treatment of improvements. Split-rate taxation still considers the value of improvements, albeit at a lower rate, while LVT solely focuses on the value of the land itself. Typically, under a split-rate tax system, the land is taxed at a higher rate compared to the buildings or improvements made on it.

California:

- Assemblymember Alex Lee, who represents California’s 24th Assembly District and has been championing both social housing and land value tax in the Golden State.

- AB362, new legislation proposed by member Lee, proposes to study the benefits of more equitable property taxation, signaling an interest in LVT.

Virginia

- Skyrocketing rents and displacement of long-time residents by an in-migration of wealthier families has led advocates like Joh Gehlbach at the Richmond Association of REALTORS® to push for LVT as a way to incentivize housing production. Because Virginia is a Dillon Rule state, legislation was required to allow Richmond to enact a split-rate tax, and SB725 passed the General Assembly 2020. The Homebuilders Association and suburban developers have voiced support, albeit with concerns about their downtown land investments.

- Three other cities in Virginia have been authorized to implement split-rate tax systems: Fairfax City, Poquoson, and Roanoke.

New York

- In New York, disputes over vacant lots, apartments, and the 421a tax break for the construction of affordable housing are never-ending, according to Iziah Thompson of the Community Service Society. Similar issues plague the property tax system, including assessment caps, higher effective tax rates on multifamily properties, and an opaque bureaucratic system.

Notable discussion between panelists focused on how LVT could be used as a tool to combat racial and economic disparities in cities, potentially fostering a more equitable distribution of wealth. There was also discussion on LVT’s potential to reduce speculative real estate behavior, incentivize development in urban cores, and create more sustainable urban environments. The importance of grassroots activism in driving the shift towards LVT was also underscored, emphasizing the need to educate the public about the benefits of this tax model.

The key challenge in pursuing a form of LVT lies in battling skepticism and communicating its advantages to stakeholders. The differences in home values in distressed city neighborhoods can pose assessing challenges, but some believe that LVT can simplify this process.

Land Value Tax presents a radical shift in how we approach public finance and urban economics. While there are potential benefits, its implementation must be carefully managed to avoid pitfalls. With the pressing issues of urban planning, housing, and economic disparity plaguing cities across the US, we’ll be keeping our eyes on the evolving discussion around LVT.