The FWD #194 • 462 Words

Can planners in the U.S. learn from zoning reforms in New Zealand?

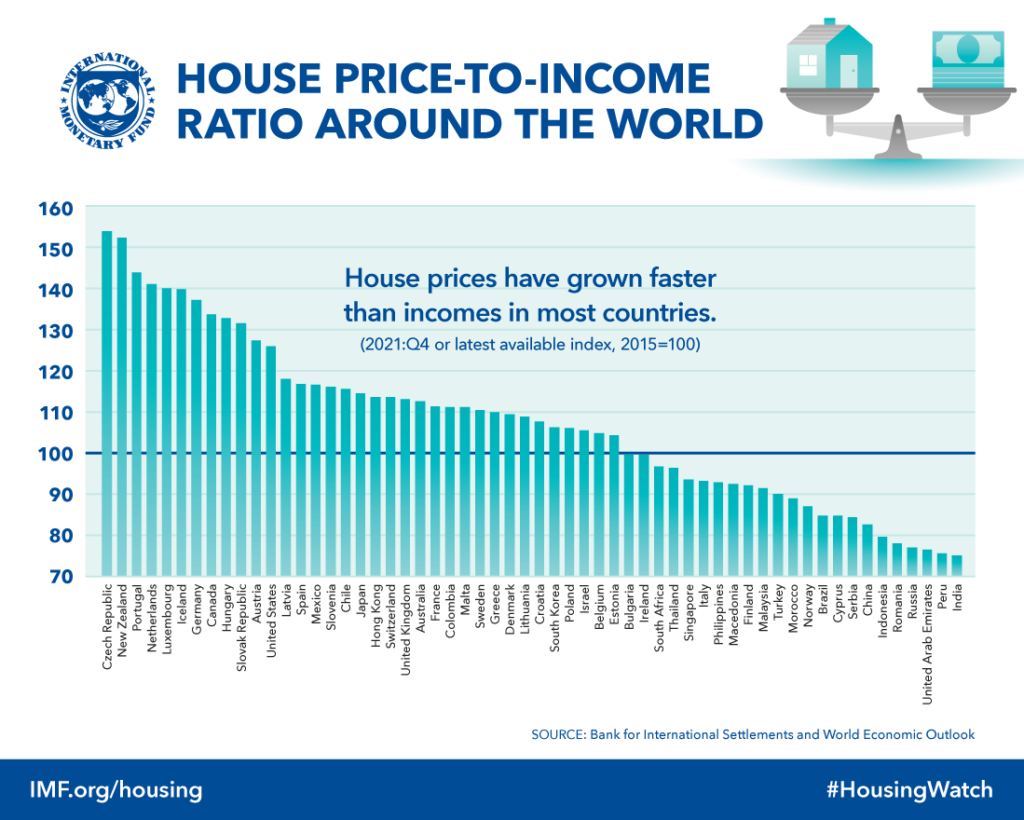

U.S. housing policy researchers short on ideas have often looked across the globe for examples of successful zoning reform efforts. The affordability crisis isn’t just an American phenomenon. In many countries, home prices have continued to outpace incomes, keeping low- and middle-income families from being able to afford safe and stable housing.

According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), of which the U.S. is a member, no other member country has experienced faster growth in real house prices than New Zealand. While the COVID-19 pandemic played a role in an overheated housing market, the lack of supply had only been compounded by decades of home construction not keeping pace with demand. Sound like a nation you know?

Rapid population growth contributed to growing demand for housing, but in the 1970s and 1980s local governments (called “councils” in Aotearoa) down-zoned areas close to urban centers. Researchers found that this policy choice led to home prices rising 69% more than they would have otherwise.

As New Zealand’s largest city Auckland was bubbling over in the mid 2010s, government leaders decided to act. In 2016, Auckland passed the Auckland Unitary Plan, which upzoned about three-quarters of its residential land, making it legal to build duplexes, triplexes, and townhomes on single-home lots. The effects of the policy were made clear in the ensuing housing boom: from 2015 to 2022, new housing permits in the city went from 9,200 to 21,301.

Moreover, upzoning also slowed rent growth. Researchers found that upzoning led to rents being 14-35% lower than what would be expected without zoning reform. In addition, home prices in Auckland only grew by 15% compared to 65% for the rest of the country from 2016.

The success of the Auckland policy inspired the national government to pass the Resource Management (Enabling Housing Supply and Other Matters) Amendment Act in December 2021 in a rare show of bipartisanship. The act requires the country’s biggest cities to allow “gentle density” in residential areas without resource consent (i.e. local government approval).

Although the National Party has since pulled back their support of the act as written, they have proposed that under a National-led government, councils would be able to choose between increasing density in urban areas or developing greenfield sites. But regardless, they would be “required to zone land for 30 years’ worth of housing demand in the ‘short term’ and, if they didn’t, central government would do it for them…”

Many people have their eye on Aotearoa—especially housing researchers. What we learn may take time as politics and market dynamics play out, but these national efforts to address housing affordability through land use policy are worth watching.